Leaf cutter ants are among the most charismatic of insect species. We enjoy watching them parade by with leaves held like parasols as they cross the jungle floor in the tropical rainforests of Central and South America. Not only do they have a festive appearance, they feature some amazing adaptations.

Leaf cutter ants are the original farmers, harvesting crops of edible fungus that they cultivate on leaf fragments. They have jaws that are highly adapted to cutting vegetation with large razor-like mandibles that they can vibrate up to a thousand times per second. They routinely carry leaf cuttings that are 20-50 times their body weight.

Fast and Fun Facts

- Leaf cutter ants don’t eat the leaves. Instead, they use the leaf cuttings to cultivate fungal growth in their nests, providing food for the ant larvae.

- The ants cut the leaves with razor-sharp mandibles that can vibrate up to 1,000 times per second

- Ants have a variety of jobs in the nest, from foragers who collect the leaves, to guards, soldiers, and dump workers.

- Minims are tiny protectors that protect the leaves and other workers from parasitic flies and wasps.

- Minims can hitchhike on cut leaves being carried by foragers and can also ride on the larger workers.

- Most leaf cutter ants are infertile female workers.

- Workers can vary in size; smaller ones work in the fungal garden, larger ones forage for leaves and the largest guard the lines of foragers.

- Lines of foragers can reach up to 100 feet or 30 meters.

- Leaf cutter ants are responsible for decomposing up to 15-20% of leaves in their home range.

- Leaf cutter ants can carry pieces in their jaws that are 20 to 50 times heavier than they are!

Interested in ants that live as farmers? Check out my article on ants that farm aphids to collect a sweet substance called honeydew.

There are over 40 species of leaf cutter ants in the world. They cut leaves into manageable pieces with their large jaws and carry the pieces back to their nest. It is fun to watch these busy ants hurry along in long processions carrying oversize leaf fragments. These lines can reach up to 100 feet or 30 meters.

Some researchers estimate that leaf cutter ants are responsible for decomposing 15-20% of all leaves in South America.

Highly efficient mandibles for cutting leaves

Leaf cutter ants need fresh vegetation – not for food – but for growing the symbiotic Lepiotaceae fungi that they feed their larvae. They harvest the vegetation by chopping leaves, stems and flowers into fragments with their large jaws and then carrying the clippings back to the nest.

In the process of cutting leaves, the ants use highly efficient razor-like mandibles that vibrate at high-frequency, up to 1,000 times per second. The vibrations, produced using a specialized organ located on the gaster, appear to stiffen the material for a smoother cut. Through natural selection over millions of years, the ants have evolved mandibles that work like high frequency jigsaws combined with razor sharp tin snips.

While cutting leaves, the adult ants feed on the sap for nourishment and energy.

Dr Robert Schofield, with the University of Oregon, has some amazing videos that show the mandibles of leaf cutter ants in action. Here’s one of his videos showing the mandibles cutting through leaf material, taken from below.

What happens when razor-sharp mandibles wear out?

Dr. Schofield and his colleagues have also discovered that the cutting mandibles eventually wear out, forcing the ants to switch jobs. Once the mandibles become dull, it takes the ants twice as long to cut through leaves while expending twice as much energy. Eventually they switch jobs from cutting leaves to carrying leaves. Not an easy switch when you think of the loads these ants routinely carry!

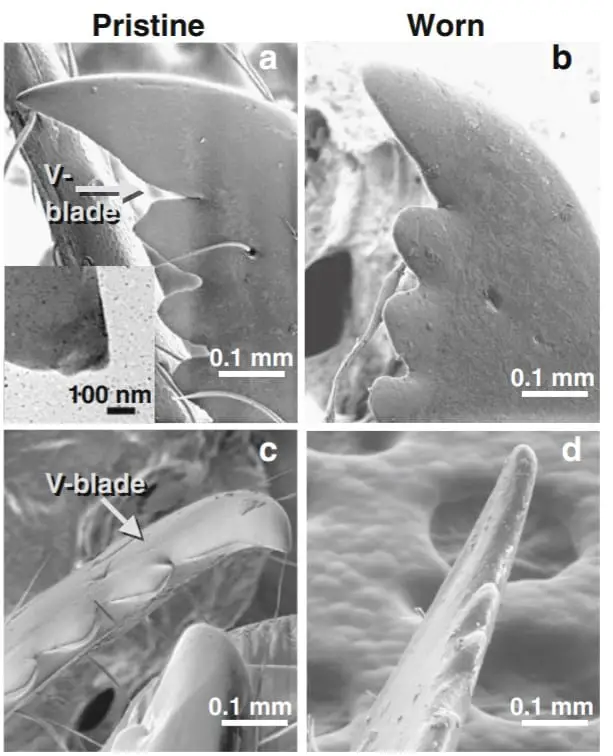

The photos below show both pristine and highly worn mandibles of one species of leaf cutter ant, A. cephalotes. The University of Oregon researchers discovered a “V-blade” between the first and second teeth that may aid in cutting through tough leaf veins. Electron microscope images show a blade radius of about 50 nm or the sharpness of a new razor blade.

Video of ant with worn mandibles having difficulty cutting a leaf

Leaf cuttings are carefully added to the farm

Once the clippings arrive at the nest, ants lick each surface. It is thought that they are decontaminating the leaves and removing any potential competitors of the cultivated fungus. Once cleaned, the ants cut, crush, and puncture the leaves and even discharge fecal liquids to break them down into suitable pieces for their fungus farms. After processing, the ants carefully maneuver each piece tightly into place.

Video of leaf processing

Fungus growers par excellence

The next step after processing the leaf fragments is to inoculate each piece with the edible fungus. This involves transferring bits of mature fungus onto new leaf fragments to spread the fungus. Once established the fungus is carefully tended until harvest time. Like all good farmers, leaf-cutter ants protect the crops from pests and mold and make certain to control any competing fungi that might try to establish in the fungus farm.

The edible fungus the ants cultivate on their leaf clippings is the main source of food for the ant larvae. Adults feed on the sap from the leaf cuttings. Each species of ant grows a particular species of fungus that can only be found in their colonies and nowhere else.

Leaf Cutter ant nests can get huge

Leaf cutter ant colonies can have up to 10 million residents with thousands of tunnels and chambers for fungus gardens, nurseries, trash heaps, and other uses.

Next to human society, leafcutter ants are considered to have one of the most complex societies on earth.

Caste system keeps every ant in line

In a mature leafcutter colony, different sized ants have different jobs and are divided into castes. Every caste has a specific function, with some remarkable behaviours.

The smallest ants, for example, the minims, will ride along on cut sections of leaf while they are carried back to the nest by the media workers. While hitchhiking, the minims will protect the leaves from parasitic flies and wasps, and work to decontaminate each fragment before it arrives at the nest, while feeding on the sap of the leaf. When the media ants are out cutting and collecting leaves, they are at risk of attack by some species of phorid flies, parasitoids that lay eggs into the crevices of the worker ants’ heads. Often, a minim will sit on a worker ant to ward off any attack.

Minims are the smallest workers and tend to the larvae or care for the fungus gardens. They are sometimes called tiny protectors, because they protect the leaves and other workers from parasitic flies and wasps.

Minors are slightly larger than minima workers and are present in large numbers in and around foraging columns. These ants are on patrol and will vigorously attack any enemies that threaten the foraging lines.

Mediae are generalized foragers, cutting leaves, and carrying the leaf fragments back to the nest.

Majors, the largest workers, act as soldiers, defending the nest from intruders. They can also take advantage of their body size by clearing trails of large debris and carrying bulky items back to the nest.

Dump workers are indispensable… but ostracized

The dump workers are older and less valued than the healthier, younger ants that work on the fungal garden.

There are two types of dump workers: waste transporters and heap workers. The waste transporters take used substrate, discarded fungus, and dead ants to the waste heap. Heap workers dig in and organize the waste, shuffling it around to speed decomposition.

The rest of the colony avoid interacting with dump workers.

Hart and Ratnieks (2001) showed that in laboratory colonies of Atta cephalotes, heap workers were subject to heightened aggression from nest mates. The researchers proposed that this aggressive response to waste-contaminated ants helps prevent waste workers from leaving the heap and thereby contaminating the fungus gardens.

Division of labor

In another fascinating study, Hart and Ratnieks (2002) marked 2,700 waste transporter ants; 200 or 7.4% became heap workers. None became foragers. Only two of 5,200 marked foragers later worked at waste disposal, both becoming heap workers. None of the 76 marked heap workers switched jobs to become transporters, and 21 were dead on the heap within two days. Some would consider that a dead-end job!

Excellent overview video of leaf cutter ants

Bonus – Zombie ants!

Leaf-cutter ants can have a nasty enemy to contend with; a deadly infectious fungus called Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. If a spore from this nasty fungus lands on an unfortunate ant and takes hold, it will turn the ant into a walking zombie! The fungus takes control and forces the ant to walk to an optimal spot in the forest – optimal for the fungus, that is! How the fungus controls ant behavior remains unknown.

When the ant reaches its destination, it bites into a leaf vein in a ‘death grip.’ Once the ant dies, its body stays in place so the fungus can grow without disturbance. The fruiting body will burst through the ant’s skull like a mushroom to release its spores into the forest, to create even more zombies. Creepy, right?!! Luckily for the ants, only about 6-7% of fruiting bodies produce viable spores.

The Gear We Love to Travel With

We love to travel in search of exceptional wildlife viewing opportunities and for life-enhancing cultural experiences.

Here is the gear we love to travel with for recording our adventures in safety and comfort:

- Action Camera: GoPro Hero10 Black – we find these waterproof cameras are invaluable for capturing the essence of our adventures in video format. Still photos are great, but video sequences with all the sights and sounds add an extra dimension. I use short video clips to spice up many of my audiovisual presentations.

- Long Zoom Camera: Panasonic LUMIX FZ300 Long Zoom Digital Camera – I love this camera for its versatility. It goes from wide angle to 28X optical in a relatively compact design. On safari in Africa I’ve managed to get good shots of lions that the folks with long lenses kept missing – because the lions were too close! I also like the 120 fps slow-motion for action shots of birds flying and animals on the move. I call this my “bird camera.”

- 360 Camera: Insta360 ONE R 360 – 5.7K 360 Degree Camera, Stabilization, Waterproof – see my article How to Take Impossible Shots with Your 360 Camera. This camera is literally like taking your own camera crew with you when you travel! Read my article and you’ll see why.

- Backpack camera mount: Peak Design Capture Clip

- Drone: DJI Mini 2 (Fly More Combo) – this mini drone is made for travel!

- Water Filtration: LifeStraw Go Water Filter Bottle

- Binoculars: Vortex Binoculars or Vortex Optics Diamondback HD Binoculars (good price)

References:

Hart, A., Ratnieks, F. 2001. Task partitioning, division of labour and nest compartmentalisation collectively isolate hazardous waste in the leafcutting ant Atta cephalotes . Behav Ecol Sociobiol 49, 387–392 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s002650000312

Hart, Adam G., Ratnieks, Francis L. W. 2002. Waste management in the leaf-cutting ant Atta colombica. Behavioral Ecology, Volume 13, Issue 2, March 2002, Pages 224–231, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/13.2.224

Hughes, D.P., Andersen, S.B., Hywel-Jones, N.L. et al. Behavioral mechanisms and morphological symptoms of zombie ants dying from fungal infection. BMC Ecol 11, 13 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-11-13

Schofield, Robert & Emmett, Kristen & Niedbala, Jack & Nesson, Michael. 2011. Leaf-cutter ants with worn mandibles cut half as fast, spend twice the energy, and tend to carry instead of cut. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 65. 969-982. 10.1007/s00265-010-1098-6.

Tautz J, Roces F, Hölldobler B. 1995. Use of a sound-based vibratome by leaf-cutting ants. Science. 1995 Jan 6;267(5194):84-7. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5194.84. PMID: 17840064

Featured photo in header: mandibles of leaf cutter ant under dissection microscope. Screenshot from YouTube video Ant Dissections 101 Mandible Manipulation by Robert Schofield.

Check Out Our TOP Articles for Even More Fascinating Creatures

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos Dangerous? Why Do They Kill People?