A trip to the Galapagos islands is like a dream come true for naturalists and wildlife enthusiasts like us. We’ve been fortunate to visit the Galapagos islands and I’ve written this article to help you prepare for a trip of a lifetime to see some of the most unique animals on the planet.

Animals on the Galapagos islands are unique because they have evolved without fear of humans. Most of the land animals endemic to these islands evolved without natural predators for millions of years. Humans did not arrive until 1535, less than 500 years ago. You can swim with penguins, walk among marine iguanas, and lounge with sea lions.

There are many places in the world where animals are no longer hunted and have consequently lost much of their fear of humans. However, the Galapagos is one of the very few places on earth where animals have evolved without having an instinctive fear of humans in the first place.

We have travelled extensively through out the world in search of wildlife experiences and photo opportunities. The Galapagos is the only place we’ve experienced where you can stand a few feet from wild animals in their native habitat without disturbing them. When you walk among the marine iguanas you have to move carefully to avoid stepping on them. Sit close to sea lions on land and they will ignore you. I’ve had a native Galapagos hawk land on a branch too close for my zoom lens!

Given its small size and isolation far out in the Pacific, the Galapagos carries extraordinary significance. The association with Darwin and evolution creates a special connection for the scientific community. The unique animal life makes it one of the most-desireable eco-tourism destinations on the world stage.

5 unique animals you must see when you visit the Galapagos

Galapagos giant tortoise

As soon as you say ‘Galapagos’ most people think of giant tortoises. In fact, there is some confusion over the origin of the name ‘Galapagos.’ Many popular articles state that the word Galapagos is an old Spanish word meaning saddle. Just to clarify, galápago is indeed an old Spanish word, but it does not mean saddle. It means tortoise.

These gentle giants are among the most iconic of the native animals in the Galapagos islands and a must-see for visitors. Instagram anyone?

These are the largest tortoises in the world, reaching 5 feet in length and up to 550 pounds.

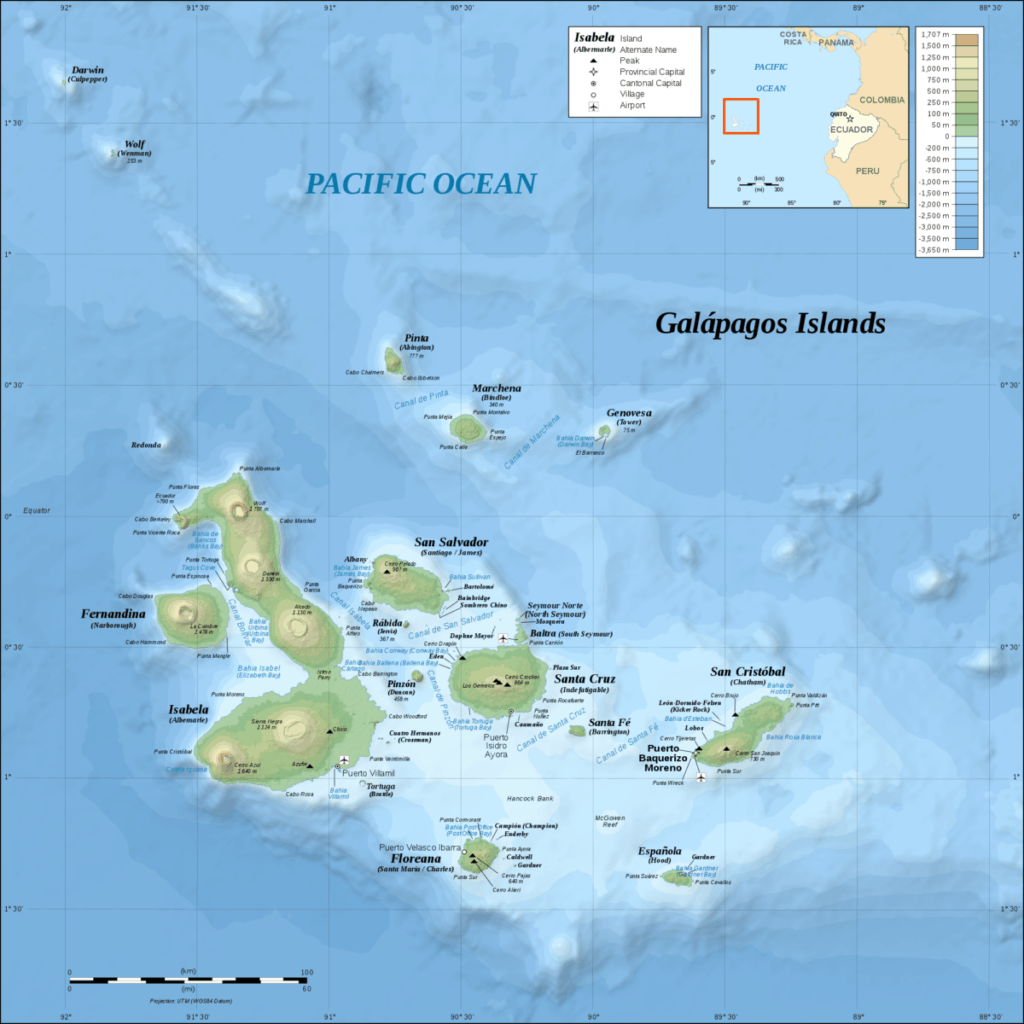

Luckily, two of the easiest spots to see giant tortoises are found on the island of Santa Cruz, the tourist hub of the islands. The first spot is the Charles Darwin Research station, on the outskirts of Puerto Ayora. You’ll find several enclosures with live tortoises and informative displays, including the skeleton of the most famous tortoise of all – Lonesome George… (see more below).

Another good place to see the tortoises is the Santa Cruz highlands. While on a half-day tour we saw several tortoises grazing in the grassy fields and wallowing in a large muddy pond. They looked like big muddy boulders, buried up to their nostrils. There’s a permanent display set up where you can touch and feel an empty carapace – and even sit on one for a sense of scale.

Of the original 15 species of Galapagos tortoise, 10 species still survive in the wild. One of the remarkable characteristics is the shape of the carapace.

Over time, tortoises have evolved into unique species on each island with distinctly shaped carapaces depending on the animal’s habits and sources of food. They fall into two categories: the saddle-backed and dome-shaped.

One of the best examples of saddle-backed was Lonesome George, with his extra long neck and exaggerated height to the front of his shell. His neck and carapace were adapted to feeding on the tall opuntia tree cactus that grows on Pinta island, where he was born. When he died in 2012, he was believed to be over one-hundred years old.

Video on Lonesome George by the American Museum of Natural History

In my presentations I like to show a photo of a long-necked tortoise beside a tall opuntia tree along with a photo of a short-necked tortoises from a different island. I raise the question: “which came first, the tall opuntia tree or the long-necked tortoise?” Answer: they evolved together!

The oldest tortoise – and perhaps the oldest animal on the planet – died at the age of 176 in 2006. Legend has it that Harriet, as she was called, was one of three tortoises taken to England by Charles Darwin on his momentous 1835 voyage. If true, Harriet was about five years old at the time and probably no bigger than a dinner plate. Think of all the experiences Harriet would have accumulated during her lifetime! If only tortoises could talk.

If you want to lead an uncomplicated life you can emulate the life of a giant tortoise. Choose a vegetarian diet (grass, leaves, and cactus), bask in the sun, and nap for nearly 16 hours per day!

Turns out that tortoises can survive for up to a year without eating or drinking, because of their slow metabolism and ability to store water internally. This fact was exploited heavily by the early sailors who reached the Galapagos islands, since they could be kept alive on board for months as a supply of fresh meat.

We know that the tortoises were extensively taken on board as food by pirates, whalers, and seamen of all sorts from the 17th to 19th centuries. Estimates vary widely on how many tortoises were taken from the islands, from one hundred thousand to millions. Records from whaling ships, for example, indicate that during the 1830s whaling vessels took an average catch of 138 tortoises on board each ship.

Non-native species such as feral pigs, dogs, cats, rats, goats, and cattle continue to threaten the tortoises’ food supply and eggs.

Marine Iguana

Marine iguanas are the only sea-going lizards in the world and another of the iconic animals you will find only in the Galapagos and nowhere else. There are sea-going reptiles such as sea turtles and the saltwater crocodile, but this is the only lizard that can live and forage entirely in the ocean. (Lizards are a sub-classification of reptiles).

When I look at my photos, marine iguanas strike me as looking like modern-day dinosaurs with their prominent scales and spiny crest. Darwin referred to them as “hideous” which I think is going a bit too far. Aren’t they so ugly they’re almost cute?!

Marine iguanas are easily seen along the shore throughout the islands. In the morning, you can find them basking on lava rocks in the sun, absorbing heat through their black scales until their metabolism allows them to swim out to sea to forage.

They don’t seem to move too quickly on land, but they are graceful and powerful swimmers. As herbivores, they feed almost exclusively on algae growing on submerged and tidal rocks. Sharp claws allow them to cling to the rocks even in big waves and surging waters. You can frequently see them sneezing liquid from their noses as they rid themselves of excess salt from their salty diet. They’ve evolved this unique adaptation since their terrestrial ancestors arrived on these islands many thousands of years ago.

We’ve noticed that the males put on a head-bobbing display that they use to warn off other males. On one occasion we saw a male head-bobbing at a female high-tailing it away from his amorous pursuit as fast as possible. He seemed to be messaging, “you don’t know what you’ve missed, babe!”

Blue-footed booby

Blue footed boobies are large sea-going birds with wingspans that reach up to 5 feet. About half of all breeding pairs are found in the Galápagos Islands.

Blue-footed boobies are one of three booby species found in the Galapagos. The name booby comes from the Spanish word ‘bobo’, meaning foolish or stupid – referring to their clumsy gait on land.

They are expert fliers and consummate fishers, soaring on their long wings in search of schools of small fish such as anchovies. I always take great pleasure in watching them dive like missiles into the sea, folding their wings back and hitting the water like a javelin.

Boobies are one group of seabirds, along with gannets, that have evolved physical adaptations necessary to plunge head first into the water at speeds of 50 mph (80 kph) or more. Without injury! Their skulls have a special air bubble to protect their brains from the force of impact. (No, I don’t think Bubble-brained boobies would be a good name.)

Why so blue?

Those feet don’t look real, do they? That color seems almost too bright. As long as boobies find that color attractive, you can bet they will continue to display blue feet!

The male booby will try to make himself even more attractive by displaying his blue feet in a high-stepping courtship dance. The pair will then extend their wings and point their blue bills to the sky, while circling around stomping and honking.

The brighter the feet, the more successful the male is in attracting a mate. Dull footed birds of both sexes find it tough going and suffer more rejections. Foot color appears to be a sexually selected trait.

Why would boobies go gaga over the brightness of their mate’s feet? Turns out that the brightness of the blue color is a good indicator of overall health. Poor hunters will have fewer carotenoids (the pigments from their food) and are likely to have dull blue feet. Better hunters have brighter feet. Turns out these birds aren’t such boobies after all!

For an in-depth look at the importance of bright colors and perfect dance moves see our article on Sexual Selection).

Galapagos Penguin

One of the best trick questions a biologist might have up his sleeve is to ask: “where do you find penguins?” An unsuspecting lay person might answer, “the polar regions,” or “Arctic and Antarctic.” This gives the biologist a much anticipated opportunity to pounce on his unsuspecting victim, by pronouncing that “haha – penguins are only found in the southern hemisphere” (a biologist who adds “you moron” is showing very poor form). An excellent come back would be, “Yes, but there is one spot where penguins can be found north of the Equator. Guess where?!” You could catch a few unsuspecting biologists with this trick question.

The answer, of course, is the Galapagos Islands! It is the only place on the planet where you can find penguins living in the Northern Hemisphere. And swimming with coral!

Penguins are one of the five seabirds found in the islands. Like most penguins, they are extremely skillful swimmers and can zoom around at high speeds with remarkable agility. One of our favorite experiences in the Galapagos is to snorkel with the penguins and to appreciate the ease with which they do high-speed loops all around us. They swim so fast that I never did get a decent photo of one underwater!

Galapagos penguins are fairly small at 20 inches long and up to 5 pounds. They feed on small fish in waters close to the islands, such as sardines, anchovies and mullet.

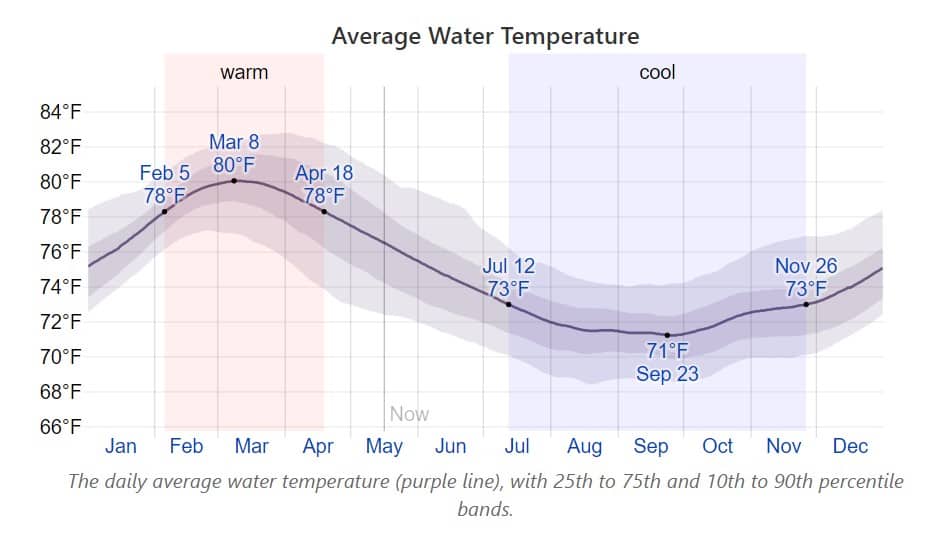

Even though they live so close to the equator, these penguins can survive in the Galapagos waters cooled by the Humboldt current sweeping northwards along the west coast of South America.

Galapagos Sea lion

The sea lion is likely the most common native mammal you will see during a visit to the Galapagos. In fact, we found it difficult to find a park bench near the seashore that was not already occupied by a lounging sea lion!

The Galapagos sea lion is a subspecies of the Californian sea lion and inhabits most of the islands, with an estimated population of 50,000.

Swimming with sea lions is a real treat, they are such graceful swimmers and the females and young can be friendly and playful. We’ve had young sea lions swim over to get a good look at us and to swim in sinuous circles all around us. Sometimes they come up close and gaze into your face with their big dark eyes.

The adults are large animals, with females weighing 200 pounds on average. Bulls, on the other hand, are even larger and weigh about 550 pounds on average and can reach up to 900 pounds.

Bull sea lions are very territorial and rather than having a harem, they will protect a stretch of shoreline where females congregate. The more successful the bull, the larger his stretch of beach, and the greater the number of females he can mate with. As you can expect, defending a territory can be very demanding. Bulls can be ‘on watch’ for days without getting much food or sleep. Other bulls are constantly testing and challenging the territory holder, and stronger, less weary, males can win the prize and take over.

You wouldn’t want to swim with a bull sea lion. In addition to their giant size, they can be aggressive towards swimmers and have been known to bite. Even on land it is surprising how quickly they can move if motivated. They can ‘gallop’ faster than a person can run, even on rocky terrain.

Galapagos sea lions feed on small fish, especially sardines. They are remarkable divers and, based on data from time-depth recorders, they can remain underwater for over ten minutes and reach depths of almost 600 m. This exceeds the diving ability of other species of sea lion, likely since the Galapagos sea lion has the lowest metabolic rate of any sea lion measured to date.

Planning a trip to the Galapagos

Planning a trip to the Galapagos can seem daunting at first. There are so many factors to consider: the season of the year, which islands to explore, to book an organized tour ahead of time or try to find a last-minute deal… to take a cruise boat or stay on land? In our case, we wanted to see natural areas and to experience as much of the wildlife as possible.

When you arrive at the main airport in Galapagos, you might be surprised to discover that you are a long way from the main town of Puerto Ayora. Seymour Airport (IATA: GPS, ICAO: SEGS) is on the the island of Baltra.

The first thing you need to do as soon as you land, is to pay your National Park fee and to get your permit organized. This takes place at the National Park desk in the airport terminal and can easily take an hour or more on a busy day.

You will take a bus to a ferry, then a short ride over to the main island of Santa Cruz, and then another bus to the town of Puerto Ayora. We found it worthwhile to arrange a car and driver ahead of time, since it is a chaotic scene when you get off the ferry and the buses and taxis can fill up.

We suggest you stay for at least one or two nights in Puerto Ayora to get your bearings. This is one of our favorite towns in Latin America, with lots to see in the town itself. The walk along the waterfront is very enjoyable with a hive of activity centered on the main dock.

The fish market is worth a stop of its own, it is so colorful and interesting with frigate birds swooping low to grab fish morsels, pelicans crowd into the enclosure, while sea lions stand among the people at the fish cleaning stations with their snouts inches from the counter tops. We saw one sea lion receive a gentle whack on its nose for getting too close.

The Charles Darwin Research Foundation is a must-see destination if you want to fully appreciate how unique the Galapagos islands are, and all the work being done to understand and protect the wildlife. You’ll find educational displays on ocean life, a whale skeleton, and a display on the most famous tortoise of all – Lonesome George. There are several enclosures with giant tortoises and land iguanas, as well as information on the native plants. It’s also a good place for a drink and a bite to eat.

When is the best time to visit the Galapagos?

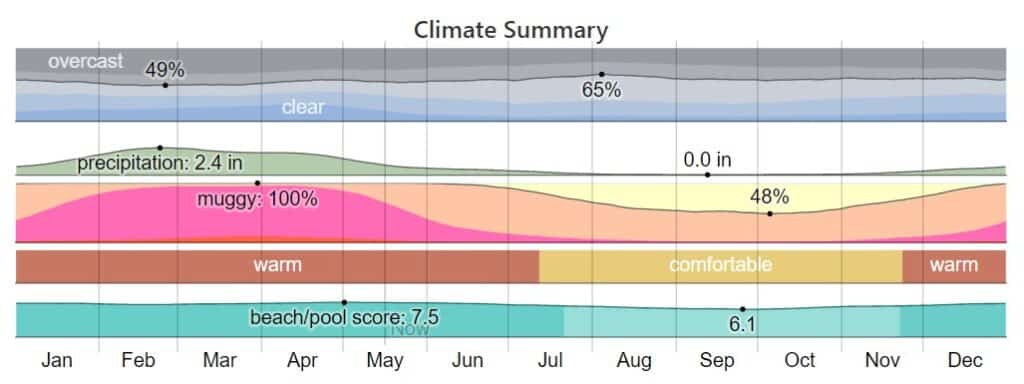

In our case, we’ve visited the islands in December. December is the beginning of the warm and wet season (December – June) and considered to be one of the best times to visit Galápagos. The seas are supposedly calmer with good visibility underwater, and rain showers are usually short. July to November can be drier but windier, with more turbulence in the ocean.

Even though the islands are on the equator, they don’t get too hot. The cool ocean currents maintain a temperate climate.

My advice… any time of year that you can make it to the Galapagos is a good time to visit.

Climate charts for Pto Ayora, Galapagos islands

Ocean temperature

One important consideration is water temperature since snorkeling can be such an attractive part of your trip. I can tell you from personal experience that even though the Galapagos islands straddle the equator, the ocean is cool because of the Humboldt current sweeping up along the coast of South America. In fact, Galapagos waters are the only place on the planet where you can swim with both penguins and corals at the same time!

Scientific importance of Galapagos Islands

Charles Darwin was one of the most famous visitors to the Galapagos and his visit was instrumental in the formulation of his theory of evolution. He recalled at the end of his life, ‘being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence. . . it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved & unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species.’

Darwin’s experiences in the Galapagos islands helped to spark one of the most profound insights ever to emerge: the role of natural selection in the formation of new species.

Resources

Visit the official Galapagos National Park website for important arrival information, national park fees, and rules for visiting.

Galapagos National Park

Charles Darwin Research Foundation official website https://www.darwinfoundation.org/en/

Galápagos Islands live cam. Go online for a view of the Galápagos giant tortoises from Semilla Verde Hotel in Isla Santa Cruz. https://www.skylinewebcams.com/en/webcam/ecuador/galapagos/santa-cruz-island/galapagos-ecuador.html

Article on Galapagos sea lions in Galapagos Matters

http://galapagosconservation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Sea-lion-article-GM-AW16.pdf

Check Out Our TOP Articles for Even More Fascinating Creatures

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos Dangerous? Why Do They Kill People?

1 thought on “Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?”

Comments are closed.