Join us on our expedition to find wild lemurs in Madagascar. Lemurs are some of the most iconic creatures on our planet and we were excited to find and photograph some rare Black Lemurs in the wild.

One of the best places to see lemurs in the wild is Lakobe Reserve on the island of Nosy Be, Madagascar. We were thrilled to find and photograph Black Lemurs in their native habitat. Madagascar is the only place to see lemurs in the wild and populations have plummeted in recent years, with many species close to extinction. Black lemurs are red-listed as vulnerable by the IUCN.

As naturalists, Madagascar has always held a special fascination for us. Lemurs are legendary in the world of biology because they have evolved to fill nearly every ecological niche on the island of Madagascar. And they are among the most charismatic creatures you will ever see! The Ring-tailed lemur is one of the most widely-recognized and cherished of wild creatures – yet, sadly, their numbers have plummeted and 95% have disappeared from the wild in recent years.

We had the opportunity to visit Madagascar on a segment of Holland America’s world cruise. As the science lecturer on board the ms Amsterdam I had given a presentation on lemurs, including the fact that they are primates but not closely related to monkeys. I enjoy highlighting the unique characteristics of wild creatures and lemurs are a gold mine of fascinating information. Our stop in Nosy Be presented a perfect opportunity to try and see lemurs in the wild and to get some photos for future presentations.

Our expedition to see lemurs in the wild

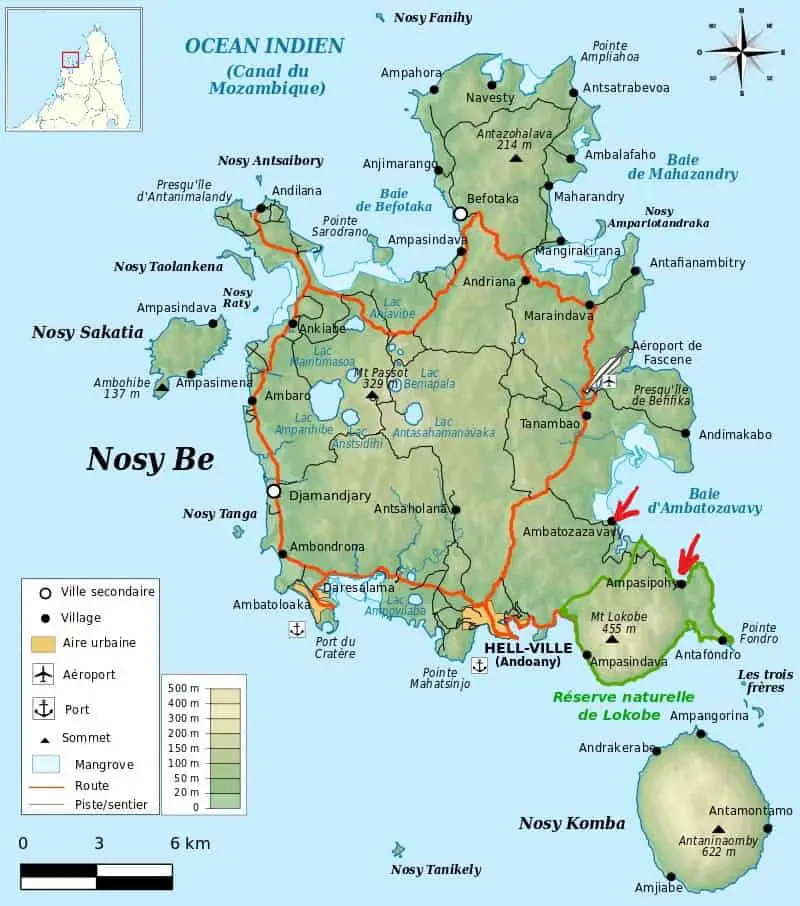

Nosy Be is Madagascar’s largest and busiest tourist resort and visited by cruise ships every year. Fellow passengers had organized a tour to see lemurs and we were invited to go along. The dock is in the largest town on Nosy Be – Hell-ville!! It certainly struck us as an appropriate name as we made our way through a sea of suspicious glances and rather tough looking characters. We were relieved to find our guides and drove off on what would become quite an adventure!

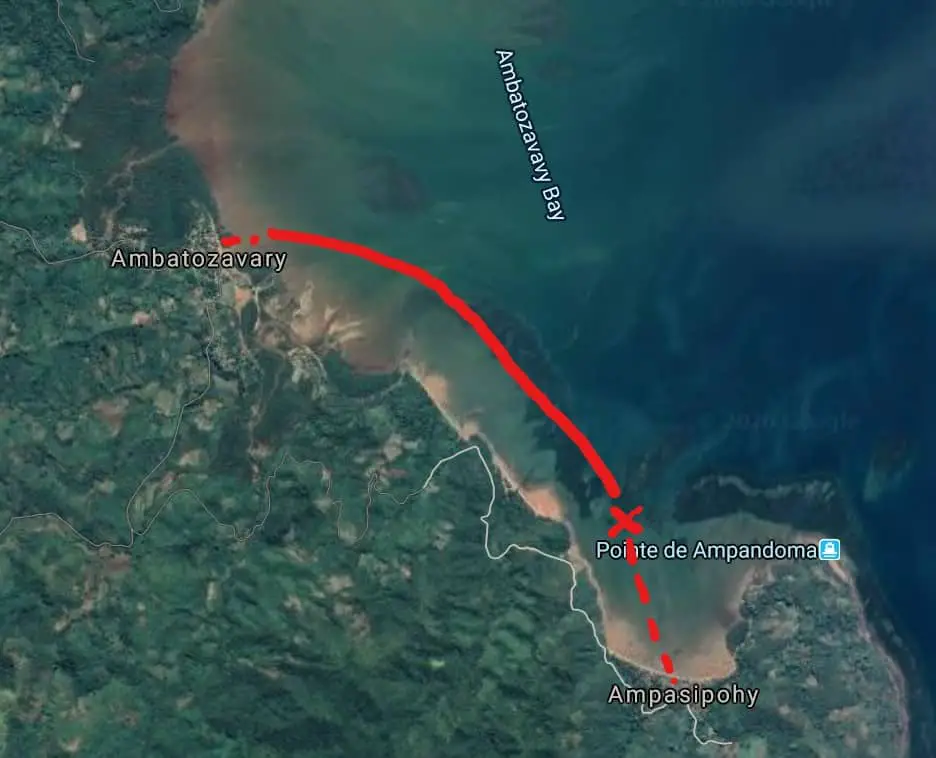

It took us nearly an hour of driving through fields of Ylang Ylang (flowers used to make aromatic oil) to reach the seaside village of Ambatozavavy. After a short stroll through the village we had a bit of a trek across exposed tidal flats before boarding typical Malagasy outrigger dugouts.

Our chief guide was constantly on his cell phone, even as we took our seats in the canoes. I joked about being a passenger, not a paddler, thinking that since we were the paying customers we wouldn’t need to lift a paddle. The joke was on me. If my wife and I hadn’t paddled, we would likely still be on that expedition! As it was it took nearly an hour of paddling before we disembarked at the village of Ampasipohy. Or rather… we disembarked onto the blazing hot mudflats that we had to cross barefoot for another 20 minutes before finally reaching dry land!

It was a treat to arrive in the authentic village of Ampasipohy. The villagers were happy to see us and had small handcrafts and souvenirs on display. You could tell that tourism was a big contributor to the local economy with people like us arriving to search for wild lemurs.

We continued through the picturesque village trailing a small band of children, smiling, and waving at the locals. Soon we were on a narrow path headed into the lush green tropical rainforest.

Lakobe Special Reserve protects a beautiful patch of native forest with thousand-year old trees, rare plants, and the sounds of insects and birds. Endemic birds include the owl of Madagascar and the Malagasy kingfisher. We soon came across a large constrictor snake looped around a branch overhead – luckily, there are no venomous snakes in Madagascar.

Then our guides spotted one of the unique and colorful chameleons that live in this region.

This was exactly the kind of nature adventure we were hoping for, with snakes, chameleons, giant spiders, tropical birds… and lemurs!

Our first sighting of a lemur was a shy nocturnal individual high up in a tree branch, trying to hide and sleep for the day. It kept an eye on our group but wasn’t about to interrupt its rest period.

A little farther along… we spotted movement in the trees. A face was peering down at us from the dense foliage in the tree above. It was our first glimpse of a black lemur!

A then we came upon a pair of black lemurs. The guides know where to find them. We had a close look and appreciated how stunning they were in real life. We watched them for 10 or 15 minutes as they watched us back. They seemed just as curious as we were. I managed to get some good photos for our collection.

Black lemurs are not all black – females are more beautiful!

The black lemur was obviously named after a male specimen. Males have black fur, while females are a lovely chestnut color. Males have black ear tufts and females have distinctive white ear tufts. They have long bushy tails.

Black lemurs are completely at home in the trees and feed largely on fruit, flowers, nuts, and insects. They are one of the most important seed dispersers in these rainforests, feeding on a wide variety of fruits in season and spreading the seeds. Their home territories are about 5 ha or 13 acres.

One interesting aspect of the black lemurs is the roaming behavior of males during the breeding season. Every now and then even a dominant male with an established group of females will suddenly leave to roam in search of other females. They will mate with females from neighboring groups as well as their own. Both dominant males and subordinates can be successful with females, although females can reject unwanted males by covering their genitals with their long tails.

What’s the difference between lemurs and monkeys?

Lemurs and monkeys are both classified as primates, as are we humans. Many people mistakenly consider lemurs to be primitive primates, but that’s not accurate. Lemurs evolved from loris-like primates roughly 63 million years ago. Monkeys evolved completely separately much later, about 42 million years ago. Lemurs have proven very successful in adapting to their environment and have filled most of the ecological niches in Madagascar.

Why are there no lemurs in Africa or monkeys in Madagascar?

Here’s the short answer to this question! Roughly 160 million years ago the island of Madagascar separated from mainland of Africa via plate tectonics and began moving steadily eastward. Early lemurs were swept by ocean currents to Madagascar on floating mats of vegetation numerous times over several million years. With the movement of continental plates Madagascar continued to drift away from the mainland, until about 20 million years ago the distance became too great for oceanic dispersal of mammals. The lemurs were isolated on the island of Madagascar, far away from the highly competitive monkeys.

When I give my presentation on lemurs in front of a large audience on a cruise ship I like to quip that “the monkeys missed the boat by 20 million years.”

Back on the mainland of Africa, once monkeys did evolve about 42 mya, they soon managed to out-compete the lemurs through intelligence and aggression. Lemurs simply went extinct on mainland Africa.

Our Nosy Be adventures continued…

After observing and photographing the lemurs in the wild, we made our way back to the village where they had prepared a big lunch for us. The lunch was excellent and more than we could eat. The guides and helpers jumped in to help clean up the food. We were eager to get moving because we faced another walk across the mudflats, paddling to the other village and then a long drive back to the port.

When you are a on a shore excursion from a cruise ship, keeping track of time is crucial. Once the last tender leaves the dock, you had better be on board. If not, the ship will leave without you! And your passport.

The guides took many precious minutes finishing their lunch, and finally we started on our way back to the ship. Malagasies are pretty laid back and our constant reminders about time constraints didn’t seem to make much of an impression. The paddle back was uneventful, but there was a strange ritual when we arrived back at the first village. Children armed with water bottles were waiting for us. They were running a small business and we were fully expected to support their endeavors. In fact, no one was going anywhere until the lads had washed the mud off our feet for an obligatory $1 per foot.

The drive back to Hell-ville took a while and the driver seemed to be in no hurry. Finally, we arrived back in town eight minutes before the last tender was scheduled to leave. Except there was a big crowd completely blocking the road. Traffic was stalled. It was a funeral procession and they were slowly making their way through town. End of discussion. In desperation, my wife pointed to an alleyway off to the right side. The driver said, “no, that’s one way!” He quickly relented and went for it anyway. We managed to circumvent the funeral procession and arrived at the dock two minutes before departure time. We had made the last tender! Hallelujah!!

The island of Nosy Be, Madagascar

Nosy Be is located on the West side of Madagascar, near the northern tip. See the inset below.

Map by Boldair, Wikimedia

Threats to the lemurs

Sadly, the situation is dire for nearly every one of the roughly 100 species of lemur. The IUCN warns that 90% of all lemur species could be extinct within 20 to 25 years unless millions of dollars are spent on conservation plans aimed at local communities.

Deforestation is the biggest threat to their survival. Most species are reliant on the native forests and only about 10% of the original forest remains.

Madagascar has been politically unstable and in crisis since 2009. Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world, and 70% of the population lives in poverty resulting in extreme levels of poaching, illegal logging, and chop and burn agriculture.

In much of Madagascar, even endangered lemurs are still hunted and killed for food – in many cases their future hinges on income from eco-tourism.

We truly hope that visits like ours help persuade villagers and politicians that there’s an economic value to protecting lemurs in the wild. One of the best things we can do to help save these fascinating creatures is to contribute directly to the local economy.

Further Information

Duke Lemur Center – top authority on lemurs

To learn more about lemurs visit the Duke Lemur Center’s website at https://lemur.duke.edu!

Check Out Our TOP Articles for Even More Fascinating Creatures

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos Dangerous? Why Do They Kill People?