Death is inevitable for male octopuses once they’ve mated because they stop feeding, they become uncoordinated, often attracting predators in the wild, and they lose the ability to heal their skin. This period near the end of life, called senescence, is driven by secretions from the optic gland that trigger the reproductive organs while inactivating the salivary and digestive glands, thereby causing loss of appetite and eventual starvation.

Most octopuses are short-lived – only living for 1-4 years. Interestingly, the optic gland is like a self-destruct system that appears to control reproduction and life span in response to environmental factors such as light, temperature, and nutrition.

Most species of octopus are “semelparous,” meaning they reproduce once and then die. Salmon are another example of a semelparous marine species.

After mating, male octopuses normally starve to death or attract predators, thereby becoming part of the food chain.

Why do Octopuses Die after Reproduction?

Wang and Ragsdale (2018) suggest that semelparity in octopuses (reproduce once and then die) is likely an evolutionary mechanism that drives post-reproductive death.

Many octopus are cannibalistic. Hatchlings from the same clutch often eat each other and females are known to kill and eat the males after mating. There is every possibility that a female octopus would eat her own young if given the chance.

Death after reproduction is a good way of ensuring that a female does not consume her own young!

Octopuses Seem to Lose Control before Dying

Octopuses near the end of life seem to lose control over their own bodies and look as if they’ve forgotten how to swim properly. They frequently lose their balance and trip over their own arms.

Senescent octopuses may even chew their own arms and bite off chunks of tissue.

What is Senescence and how does it Work?

Senescence is a period of at the end of life when the functional characteristics of living organisms gradually deteriorate. Senescence represents the last part of an animal’s lifecycle before it dies.

With octopuses, senescence is triggered by reproduction and ends with the animal’s death.

According to Anderson et al. (2002) the are four conditions or activities that can be used as indicators of octopus senescence:

(a) loss of appetite and lack of feeding, leading to weight loss,

(b) retraction of the skin around the eye,

(c) undirected or uncoordinated activity, and

(d) the occurrence of white lesions on the skin.

The loss of appetite in both male and female octopuses during senescence is well documented, and it appears that fasting inevitably leads to death by starvation.

When Octopus Eyes Grow Large, the End is Near!

When octopuses stop eating in senescence, their eyes stay the same size while the body shrinks as the animal loses weight. This causes the skin around the eyes to retreat, making the eyes look bigger.

Both Male and Female Octopuses experience Senescence

For the female octopus, life after mating is characterized by an extreme dedication to caring for her eggs. During the brooding process, she will clean and protect her eggs without feeding until her death – for months or even up to a year – losing between 50-71% of her body weight.

Unlike females, male octopuses don’t provide any clear signals that they’ve entered senescence. The best sign that males are becoming senescent is their lack of appetite. They stop eating, and their bodies begin to deteriorate.

What Role does the Optic Gland play in Senescence?

The optic gland between the octopus’s eyes is somewhat analogous to the pituitary gland in humans.

In a key experiment (Wodinsky (1977), researchers removed optic glands from female Caribbean two-spot octopuses (O. hummelincki) that were brooding their clutches of eggs and had stopped feeding.

The females suddenly lost their maternal instincts and abandoned their eggs. They resumed feeding, gained weight and some even mated again. They went on to live a much longer life, nearly 6 months longer than their counterparts with the intact optic glands.

Wang and Ragsdale (2018) conclude that rather than secreting a single hormone, “the optic gland likely enlists multiple signaling systems to regulate reproductive behaviors, including organismal senescence.”

For octopuses, it turns out that the optic glands and optic gland secretions constitute something like a ‘self-destruct system’ ensuring death after reproduction.

How long Can Male Octopuses Survive without Eating?

Males can survive a surprisingly long time without eating. At the Seattle Aquarium, male great pacific octopuses stopped eating for 14 to 76 days (48 day mean) and lost 4.3% to 32.1% of their body weight (a mean of 17.4%) before dying.

Senescence was monitored in three male O. vulgaris at the Konrad Lorenz Institute. They stopped eating for periods of 79 to 188 days before dying (mean of 131 days). They did not stop eating suddenly but gradually ate less and less. Two of these octopuses exhibited small white lesions for long periods (248 and 257 days) before their deaths, with the lesions increasing in number and size prior to death.

Another octopus, O. macropus, died 165 days after his last mating. During this time, he rarely ate food, and was never seen during the day. He did emerge to become very active at night, swimming and jetting around his tank.

Male Octopuses become More Active During Senescence

In the wild, the uncoordinated and undirected activity of a senescent male octopus is likely to get him into trouble by exposing him to predators.

Male octopuses show increased activity at the start of senescence, but it is largely random and undirected and doesn’t appear to be related to hunting or foraging. Studies on the activity patterns of Octopus vulgaris at the Konrad Lorenz Institute showed that senescent males were statistically more active than normal males.

In an aquarium setting, the undirected activity of senescent males should not be confused with the repetitive pacing-like activities of bored octopuses. Bored octopuses respond well to proper enrichment if given the right opportunities, but senescent octopuses never return to what could be considered ‘normal.’

As an interesting side note, senescent males are much more likely to escape from captivity because of their increased activity during this period.

How Long do Octopuses Live?

If octopuses had a motto, it might be to “live fast and die young!”

(Borrowed from the Hell’s Angels and applied to cephalopods by O’Dor and Webber (1986)

Most octopus and squid tend to be short-lived, with natural lifespans of only a year or two, and possibly up to four years. In many ways this is surprising, since some mollusks can live for many years. Several gastropods (snails) and bivalves (clams) have been reported to live for more than 50 years.

Within a matter of months octopuses are born, they mature, they mate, and then they die. Females brood eggs, but once the eggs are hatched, they die. During the brooding period, female octopuses can keep their metabolic rate unnaturally high, even while starving, by metabolizing muscle tissue as fuel.

Here’s a Deep Thought!

If octopuses had a different lifecycle, they might be running the world!

The main reason they aren’t (running the world) boils down to the fact that they are short-lived and don’t stick around long enough to teach their young after hatching. They breed and die. This means that each generation must learn to survive on its own without having the benefit of parental wisdom and guidance.

Cephalopods first emerged during the Cambrian, a period of great marine animal diversity over 500 million years ago (mya). Humans have been around for a couple of million years – and modern humans for only 300 to 400,000 years.

Octopuses may have lots of brain power, but they have no way of passing on their wisdom to younger generations.

If octopuses could pass on their life experiences through intergenerational learning, this world might be a very different place… with octopod masters!

See my article on why octopuses are the most intelligent invertebrates with 9 brains!

Are Octopuses Mollusks or Cephalopods?

They are both. Octopuses are in the class Cephalopoda that belongs to the phylum Mollusca, a group that includes snails and clams. It is difficult to believe that octopuses really are related to clams; in many ways they are highly evolved, super-intelligent, super-charged cousins of clams!!

Cephalopods are a diverse class of marine mollusks that includes octopuses, squid, cuttlefish, and nautiluses. They represent the most complex class in the phylum Mollusca, in terms of both morphology and behavior.

Cephalopoda means “head foot” in Greek, and their head and foot are completely merged, with a ring of arms and/or tentacles that branch directly from the large head and surround the mouth. Since they don’t have any skeletons or joints to worry about, cephalopods can flex and move in any direction due to a complex arrangement of muscles and connective tissues.

Fascinating Facts about Cephalopods, including Octopuses:

Cephalopoda means “head foot” in Greek.

The word octopus comes from the Greek, októpus, which means “eight foot.”

About 800 living species of cephalopods have been identified, with new species being discovered every year.

Cephalopods have the most complex brains of any invertebrate, marine or terrestrial. In fact, they have nine brains! Each arm has a mini-brain that can direct the arm independently from the central brain! (If you only have one brain don’t feel too discouraged. Reading this kind of stuff can create new neurons!)

All cephalopods are predators, hunting and killing their prey for food.

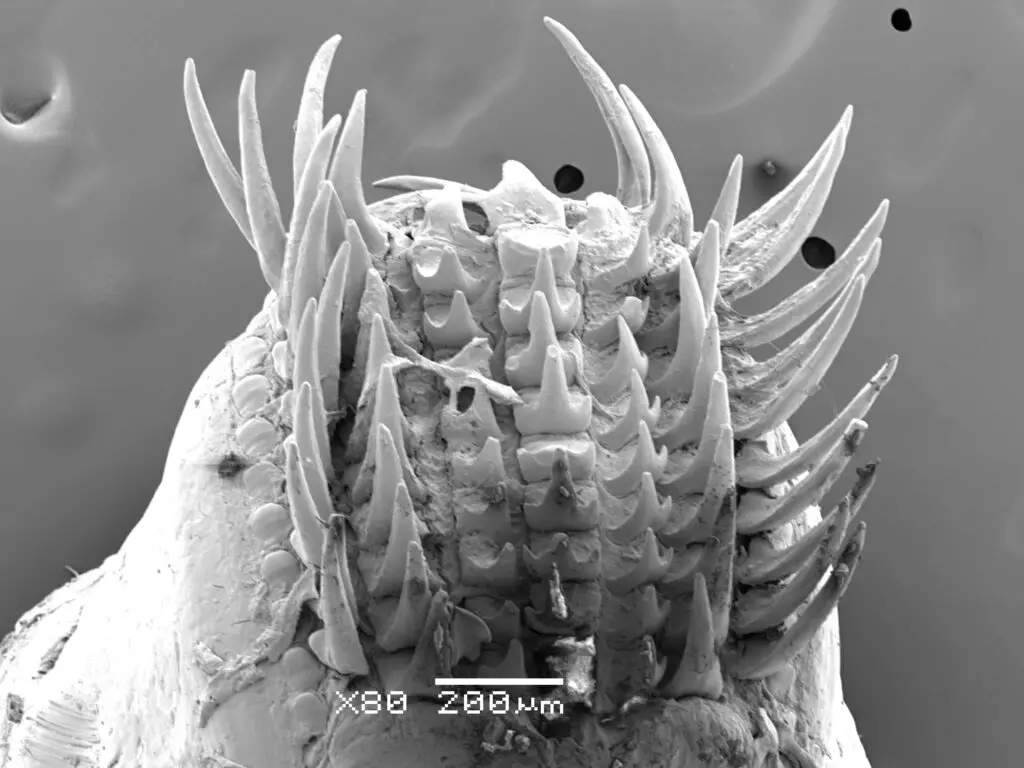

Octopuses have toothed papillae on their tongues, used to drill through the shells of crabs and crustaceans, their favorite foods. They inject venomous saliva to kill the prey and to help break down the tissues. For more on this see my related article How Do Octopus Kill Their Prey? Can an Octopus Sting You? (Beaks and Venom).

Cephalopods have relatively short lifespans of 1 to 3 years. Nautilus is an exception since it can live 16 years or more. Another unique feature of the nautilus is its detachable penis.

Male octopuses can have an erection. The tip of their mating arm, called the hectocotylus, can become engorged when the animal becomes aroused. See my article How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex and a Detachable Penis)

Want to know more about octopuses?

Check out the rest of my in-depth articles on these fascinating creatures:

Why do Octopus have 3 Hearts, 9 Brains, and Blue Blood? Smart Suckers!

How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex and a Detachable Penis)

How Do Octopus Kill Their Prey? Can an Octopus Sting You? (Beaks and Venom)

How Smart are Octopuses? (Are Octopuses As Intelligent as Dogs?)

Can Octopus Arms Grow Back? (Are Regenerated Limbs Just as Good?)

References

Anderson, Roland & Wood, James & Byrne, Ruth. (2002). Octopus Senescence: The Beginning of the End. Journal of applied animal welfare science: JAAWS. 5. 275-83. 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0504_02.

Cephalopodceramist.wordpress.com. Cephalopod Radula under the scanning electron microscope (SEM). http://blogs.evergreen.edu/cephalopodresearch/heterodont/ Accessed Feb 25, 2022.

O’Dor, R.K., and Webber, D.M. (1986). The constraints on cephalopods: why squid aren’t fish. Canadian Journal of Zoology. Vol. 64(8):1591-1605. DOI: 10.1139/z86-241

Tanabe, Kazushige, & Fukuda, Y., (1999). Morphology and Function of Cephalopod Buccal Mass. Functional Morphology of the Invertebrate Skeleton, Edited by E. Savaszzi. Chapter 19

Wang, Z. Y. and Ragsdale, C. W. (2018). Multiple optic gland signaling pathways implicated in octopus maternal behaviors and death. J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb185751.

Wodinsky J. (1977). Hormonal inhibition of feeding and death in octopus: control by optic gland secretion. Science 198, 948-951. 10.1126/science.198.4320.948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The Gear We Take With Us

We love to travel in search of exceptional wildlife viewing opportunities and for life-enhancing cultural experiences.

Here is the gear we travel with for recording our adventures in safety and comfort:

- Action Camera: GoPro Hero10 Black – we find these waterproof cameras are invaluable for capturing the essence of our adventures in video format. Still photos are great, but video sequences with all the sights and sounds add an extra dimension. I use short video clips to spice up many of my audiovisual presentations.

- Drone: DJI Mini 2 SE – this mini drone is made for travel! Roughly the same weight as a smartphone. In the United States and Canada, you can fly this drone without the need to register with local government. The lightweight and powerful DJI Mini SE camera drone is the ideal for creators on the move. The ultra-portable design allows you to effortlessly capture unforgettable scenes.

- Long Zoom Camera: Panasonic LUMIX FZ300 Long Zoom Digital Camera – I love this camera for its versatility. It goes from wide angle to 28X optical in a relatively compact design. On safari in Africa I’ve managed to get good shots of lions that the folks with long lenses kept missing – because the lions were too close! I also like the 120 fps slow-motion for action shots of birds flying and animals on the move. I call this my “bird camera.”

- 360 Camera: Insta360 ONE R 360 – 5.7K 360 Degree Camera, Stabilization, Waterproof – see my article How to Take Impossible Shots with Your 360 Camera. This camera is literally like taking your own camera crew with you when you travel! Read my article and you’ll see why.

- Backpack camera mount: Peak Design Capture Clip

- Water Filtration: LifeStraw Go Water Filter Bottle

- Binoculars: Vortex Binoculars or Vortex Optics Diamondback HD Binoculars (good price)

See Our TOP Articles for More Fascinating Creatures

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- How Smart are Octopuses? Are Octopuses As Intelligent as Dogs?

- Why are Hippos so Aggressive? Why do they Kill People?)

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?