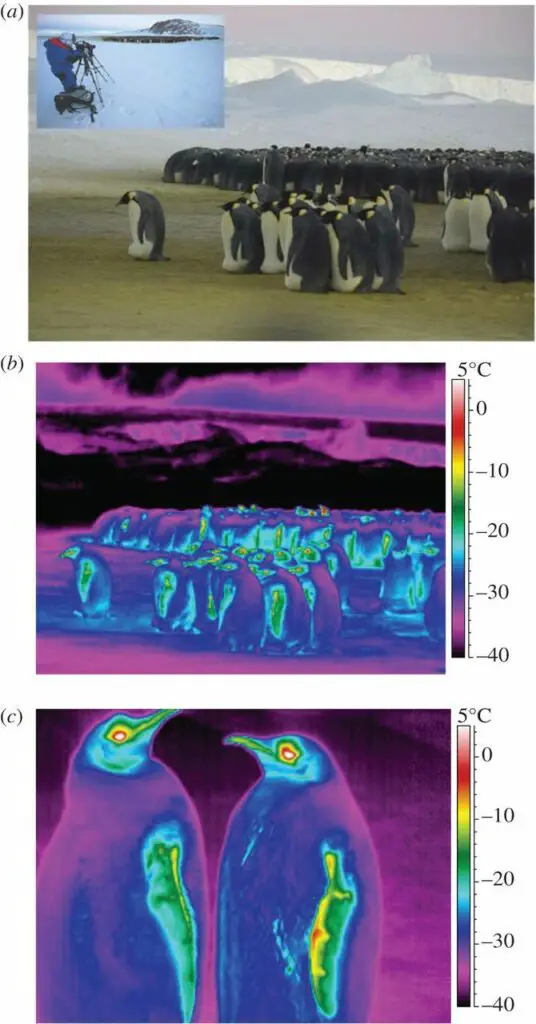

Penguins are superbly adapted to staying warm in sub-zero temperatures. They use vasoconstriction of blood vessels under the skin to prevent losing heat to the outside. Penguin feet don’t freeze because they have dense, scaly insulating pads. They also have a specialized network of blood vessels that act as a heat transfer system. Descending blood vessels in the legs transfer heat directly to colder blood returning from the feet, retaining heat within the body core. Emperor penguins huddle together in large groups to survive harsh Antarctic winters.

Penguins spend much of their lives in direct contact with ice and snow at temperatures that would freeze human skin in minutes.

How do Emperor penguins prevent frostbite when they stand on ice for months on end? How do they survive Antarctic winters when temperatures regularly plunge below −60°F (−50°C)?

As a biologist, questions like this really grab my attention! I’ve delved deep into the science of penguins to find some fascinating facts that you can share with friends and family.

Here’s my challenge to you. Try spending four months standing on solid ice with your bare feet at minus 30 degrees with occasional hurricane force winds while juggling an egg on top of your feet as you shuffle around being jostled by thousands of others doing the same thing. Welcome to the world of the Emperor penguin!

Feathers and Fat: First Line of Defense Against the Cold

Penguins are uniquely adapted to staying warm in extreme environments.

- They have multiple layers of densely packed overlapping feathers to help keep them warm and waterproof.

- Emperor penguins have several layers of scale-like feathers – it takes very strong winds (over 68 mph or about 110 kilometres per hour) to get them ruffled.

- They also have a thick layer of fat underneath their skin, as well as insulating layers of fat around the internal organs to protect them from frigid waters while swimming.

- Penguins living in the coldest parts of Antarctica have feathered legs to conserve heat.

- Extensive areas of black plumage absorb heat from the sun.

- Penguins often rock back on their heels, lifting their toes off the ice while balancing on their stiff tail feathers to get the absolute minimum area of flesh exposed to the freezing surface.

And this is just the beginning. Penguin adaptations to cold go much deeper than these initial observations. Let’s dive into some physiology!

Adaptations to the Circulatory System

One of the big secrets to survival under extreme Antarctic conditions involves adaptations to the penguin circulatory system. Like all birds, penguins are warm blooded, known as homeotherms, meaning their body is kept at a near constant temperature whatever the temperature outside.

Penguins must circulate warm blood throughout the body and to the extremities, while conserving core body temperature as much as possible. This can be tricky when outside temperatures reach minus −58° F (−50° C) and below!

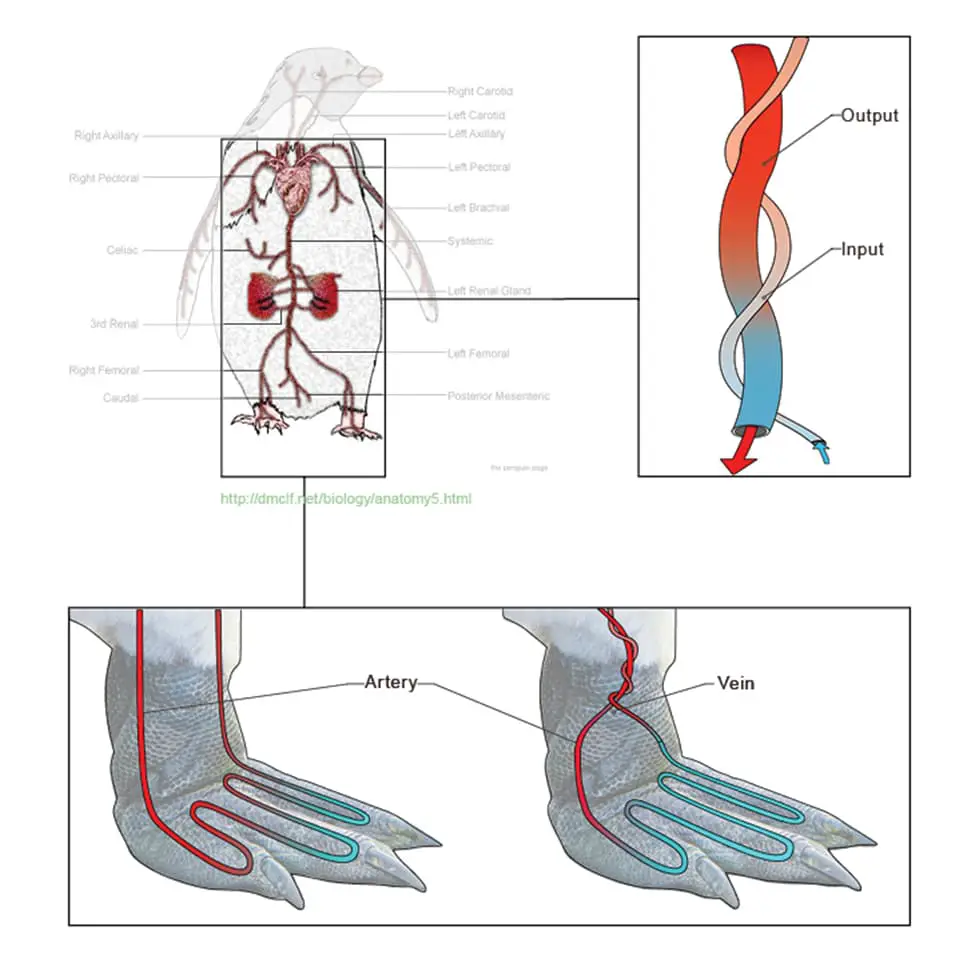

Two adaptations to the circulatory system help accomplish this: vasoconstriction and counter-current heat transfer.

Vasoconstriction

This adaptation involves narrowing the blood vessels under the skin so that less blood flows through them. During cold conditions, a penguin can control the rate of blood flow by varying the diameter of arterial vessels supplying the blood.

This reduction of blood flow near the skin surface prevents loss of body heat to the outside.

Penguins also utilize this system with the blood vessels that branch out to the feet and flippers. By narrowing the blood vessels, less warm blood passes through the feet or flippers to become chilled by freezing temperatures on the outside.

However, there’s a danger with too much vasoconstriction. If the reduction in the blood flow to the extremities is too extreme, they can get super cold to the point where the liquid inside living cells starts to freeze, causing frostbite.

Penguins have achieved a fine balance: utilizing vasoconstriction to the point where they can maintain their core body temperature without sacrificing their extremities to frostbite.

Counter-current Heat Transfer

Even when penguin feet are in contact with frozen surfaces, they don’t freeze.

Pumping warm blood through their feet would cause the heat to radiate away into the ice and snow. To prevent this, penguins make use of a system known as the counter-current heat exchange.

Heat exchange involves a clever arrangement of arteries and veins in the legs. Arteries from the heart carry warm blood towards the feet. As they descend through the legs, they split into thinner blood vessels that wrap around the veins returning with cold blood from the feet.

Using this method, blood that flows towards the feet transfers much of its heat into the blood flowing back into the body.

This important adaptation ensures that the heat from the descending blood is transferred directly to the cold returning blood, bypassing the feet all together.

Not only does this maintain the core body temperature but by limiting how much heat gets sent to the feet the penguins can reduce the amount that’s lost to the outside air keeping their cells above freezing to avoid frostbite.

Penguins also have thick, scaly pads on the bottom of their feet that provide insulation even when in direct contact with ice or frozen ground.

How Do Emperor Penguins Endure Months of Extreme Cold?

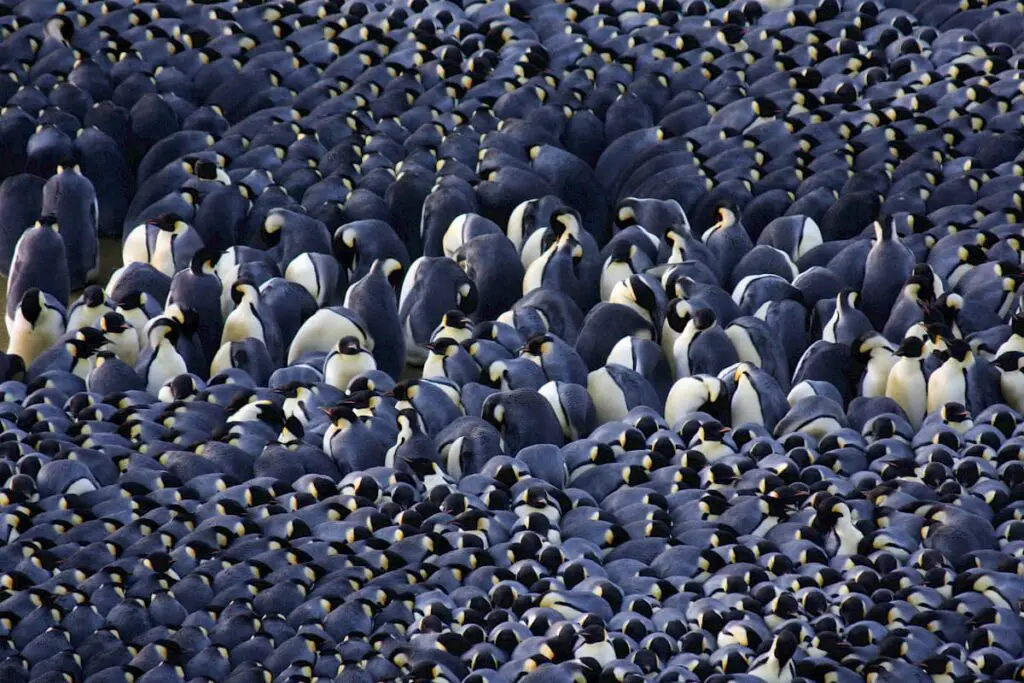

Every year, despite the harshest winter conditions on earth, male Emperor penguins huddle together in large groups on the sea ice, while balancing eggs on their feet.

Emperor penguins are the largest of all the penguin species, standing 47 inches tall (1.2 m) and weighing up to 100 lbs (45 kg).

Emperors have some unique behavioral adaptations to be able to raise chicks in the middle of the harsh Antarctic winter while sitting on ice for four months without anything to eat. The emperor penguin is one of the toughest birds on the planet, surviving the most extreme weather conditions out of 18 species of penguin.

Imagine the conditions; its dark and freezing, with temperatures as low as −58° F (−50° C) and occasional hurricane-strength winds of up to 125 mph or 200 kilometers per hour.

Facing conditions that could easily kill a human in minutes, emperor penguins do what they must to give their chicks the best possible opportunities for survival.

Timing is Key

Why would male penguins choose to stand on ice in freezing temperatures during the middle of the winter while juggling an egg on top of their feet?

It all comes down to timing.

The entire emperor penguin calendar revolves around getting the chicks ready to enter the ocean for the first time during the warmest part of year. For this timing to work, the cycle of mating and rearing chicks must begin in April (autumn in the Antarctic).

Consequently, every year in April, Emperor penguins gather in large groups on the sea ice to begin courtship and breeding. I won’t get into courtship details in this article, but let’s say it takes a lot to impress a female penguin! If they want to mate, males must learn all the right moves, practice the most impressive vocalizations, and perhaps even give gifts – see my article on what it takes to attract the right mate.

After mating, female emperors lay their eggs in May, and then return to the sea to fatten up on seafood. Meanwhile, the males stay behind to protect the eggs for four months without feeding through the long, bitterly cold Antarctic winter.

The females finally return in July, well fed from hunting and in prime condition. Meanwhile the males have lost nearly half their body mass and are downright skinny. Males and females call to one another and it is remarkable how quickly a female can identify and locate her mate among thousands of other penguins.

The pair perform a tricky transfer of the egg or tiny chick from the male to the female. Males are reluctant to leave but they are almost starving and need to go to the sea to feed.

The chick rearing period is a very busy time in the colony, with both parents taking turns brooding their chick until it can stand on the ice by itself. There’s a lot of noise and activity, with the parents coming and going and calling to the chicks, and the chicks acting as if they are continually starving.

Emperor Penguin Survival Tricks

Emperor penguins are well-equipped to face the cold: they have four layers of overlapping feathers that provide excellent protection from wind. They also have thick layers of fat that trap heat inside the body.

Even though they have such superb adaptations, Emperor penguins live under some of planet’s most extreme conditions. It’s almost inevitable that they will lose body heat at minus 50° C and colder.

Surprisingly, scientists found that the core temperatures of adult emperor penguins can drop by up to 15° C during the coldest times.

For most animals, including humans, a drop of 15° C in core temperature would be life-threatening.

Emperor penguins, however, demonstrate another neat survival trick. By letting their whole body cool to this degree (punny, huh?) they can slow their metabolism. A slower metabolism helps the penguins save energy, one key to surviving the long and bitterly cold winters.

Another adaptation to keeping warm becomes evident when you look at the photo below. Think body proportions. Doesn’t an emperor penguin’s body look too big for its head and feet?

The Emperor Huddle – Another Trick for Staying Warm

To stay warm and conserve energy during the breeding season, emperor penguins form huddles, with thousands of birds packed close together.

Emperor penguins don’t use a nest for breeding, and, unlike most other species of penguin, they don’t have individual territories. The allows them to gather in dense clusters with thousands of individuals, called a huddle, for protection against freezing temperatures and bone-chilling wind.

Surprisingly, penguins in the center of a huddle can find it too warm!

Huddling occurs most frequently during the breeding period in the winter. Scientists have found that the surface temperature of penguins in the centre of a huddle can rise by as much as 37 C within less than two hours.

In an effort to find a comfortable temperature, penguins in a huddle are usually in motion. This means that the individuals at the centre of a huddle are shuffling their way outwards to cool down, while the individuals at the outer windward edge of a huddle shuffle their way around the outside to the leeward side to warm up. Despite having an egg balanced on their feet, penguins in a huddle are almost constantly on the move.

Unlike other penguin species, male emperors incubate a single egg on their feet, by covering it with an abdominal pouch to keep it warm.

The tricky part for the male is to walk while balancing an egg on its feet without allowing the egg to touch the ice and snow for even an instant. It’s more of a shuffle really. As you can imagine, progress is slow with small, careful steps. Even when the chick hatches, the adults will continue to keep it protected as much as possible under the pouch and sitting on top of their feet.

For a good look at the dynamics of a huddle, check out this excellent video by PBS:

On windy days, those on the windward edge are most exposed to the extreme wind-chill – and bone-chilling cold. Slowly they shuffle, egg on feet, down the outer flanks of the huddle to join in again on the leeward side. Following one another, they form a continuous procession, passing through the warm centre of the huddle and eventually returning back to the windward edge.

Because they are packed so close together, just one small step can set off a wave of motion that passes through the huddle. This wave moves like cars in a traffic jam (Gerum et al 2013).

Both Emperor Parents Help Raise the Chicks

When the females return at the beginning of spring, both male and female will take turns keeping the little chick warm. But only the males incubate the eggs until hatched.

Emperor chicks look like birds that have somehow managed to get hold of thick, grey sheepskin coats that make them look like overstuffed plush toys. They have a completely different appearance from the adults and you wouldn’t be the first to suggest that they look like a different species.

Once they’ve grown to a good size, the penguin chicks gather to form little huddles of their own to keep warm.

For a heart-warming story about emperor penguin chicks banding together for survival, watch this excellent 2 min. video by the BBC.

Fun Facts About Penguins

- Penguins live throughout the southern hemisphere, not just in Antarctica. They can be found in the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Peru, and Chile.

- Some penguins worry more about heat than cold! Species such as the African penguin and the Galapagos penguin live in warm climates, even though the water they swim in is still typically cold. The specialized heat exchange system discussed above can also serve to cool the blood when they become too warm.

- The Galapagos penguin is the only species of penguin that ventures north of the Equator and only in tiny numbers.

- Where in the world can you snorkel with coral and penguins at the same time? You guessed it, the Galapagos islands.

- If you see a picture of penguins and polar bears together, someone is pulling your leg! Such a scene could never happen in nature. Polar bears live far north in the Arctic.

- A group of penguins in the water is called a raft but on land they’re called a waddle! Good name considering the penguin’s typical gait.

- The emperor penguin and the Adelie penguin both live and breed in the Antarctic – which makes them tough birds, even by penguin standards!

- Emperor penguins are good walkers. They can march up to 60 miles or more across sea ice to get to their breeding grounds!

- Human females appreciate diamonds. Female penguins prefer rocks. In some species, such as Rockhopper penguins, the males have discovered that females often respond favourably when presented with rocks during courtship. It’s a very practical gift, after all. The ladies use these rocks to build nests.

Did you know that penguins, like all birds, are literally living dinosaurs!? We have rock-solid proof in the form of fossils. Read my article presenting the Latest Science on How Birds Evolved from Dinosaurs.

References

McCafferty D. J., Gilbert C., Thierry A.-M., Currie J., Le Maho Y. and Ancel A. 2013. Emperor penguin body surfaces cool below air temperature. Biol. Lett.92012119220121192 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1192

Gerum R. C., Fabry B., Metzner C., Beaulieu M., Ancel A. and Zitterbart D.P. 2013. The origin of traveling waves in an emperor penguin huddle. New Journal of Physics, Volume 15, December 2013

See Our TOP Articles for Even More Fascinating Creatures

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- How Smart are Octopuses? Are Octopuses As Intelligent as Dogs?

- How do Electric Eels Shock Their Prey? Can an Electric Eel Kill You?

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos Dangerous? (Do They Attack People?)