Big shifts in environmental policy can be confirmed by the money and resources spent on instituting the policy decisions through statutes, regulations, agreements, and policy statements. Policy changes are only meaningful when they carry the legislative force of the state. Anything less is mere talk and wishful thinking.

In this article I will consider two high profile case studies where new commitments were made by both state and non-state actors: the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement in BC, Canada, and the South East Queensland Forest Agreement in Australia. In both cases, substantial government resources were dedicated to facilitating implementation of the policy changes.

Dedication of government resources is the only valid indicator of true policy change as far as I am concerned.

Visualizing Policy Change – Feel Free to Adopt My Model

My field of academic study is focused on environmental governance and collaborative policy change in response to intractable resource conflict.

Resource conflicts are often messy scenarios with a lot of different actors involved, including government institutions, NGOs, regular citizens, policy entrepreneurs, and rabble rousers.

In these case studies I provide a graphic depiction of the policy changes that occurred as a way of concisely communicating key influences and outcomes.

If you are involved in resource conflicts of your own, you might be interested clarifying the issues by adopting this model, or adapting it to your own needs.

A note on conflict

Contrary to common attitudes about conflict being almost exclusively negative, Dryzek (1996:481-82) views an oppositional civil society as a vital impetus for democratization and, counter intuitively, he argues, a degree of exclusion by the state can lead to a more robust democracy. He contends that an “examination of the history of democratization indicates that pressures for greater democracy almost always emanate from oppositional civil society, rarely or never from the state itself” (1996:476).

Some degree of conflict can improve the quality of solutions reached during social interaction, particularly when combined with, or setting the stage for, some level of cooperation.

Case Study: The Great Bear Rainforest Agreement

British Columbia, Canada

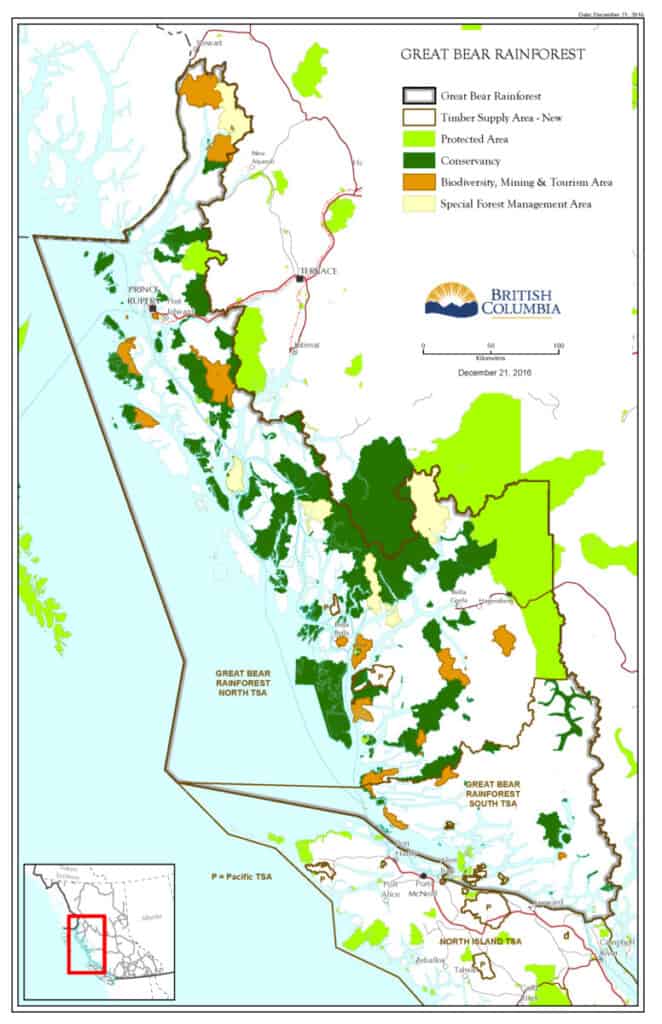

In April 2001, an internationally recognized consensus agreement for sustainable management of the Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) on the west coast of British Columbia (Canada) was signed by forest companies, environmental groups, First Nations and the provincial government, after years of intractable conflict.

The 2001 agreement represents the first widescale change in government direction oriented towards the sustainable management of the GBR. It wasn’t until 2016 that the B.C. government enacted the Great Bear Rainforest Land Use Order and the Great Bear Rainforest (Forest Management) Act to legally implement the new management regime.

Forest land use policy in British Columbia, including the GBR (Central Coast) region has been extensively researched and analyzed by numerous scholars over the decades since the 1990s.

Given the comprehensive nature of the literature, I’m focusing this account on the 2001 consensus agreement and the discourse that occurred between competing coalitions, the collaborative processes that eventually evolved, and government’s response to stakeholder consensus.

Complex Realities of Land Use in the Great Bear Rainforest

The story of the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement (GBRA) is one of institutional inadequacy in response to economic adjustment, domestic and international civic engagement, market pressures, and a strengthening biodiversity and sustainability discourse.

Conflict escalated to intractable levels in this region in the 1990s as forest industry and the BC government continued to operate under an established industrial forestry paradigm that privileged development over conservation, while environmental groups successfully mobilized public support for the protection of globally significant old growth forests.

Face-off in Clayoquot Sound

The very visible and highly publicized face-off between environmentalists and the entrenched development coalition in Clayoquot Sound set the stage for BC forest policy discourse in the 1990s. During the summer of 1993, over 9,000 protesters from all walks of life joined blockades to protest against plans to clearcut old-growth forests in the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Nearly nine hundred environmental supporters were arrested and charged, and most were found guilty of violating the B.C. Supreme Court injunction supporting the right of forest companies to continue cutting old-growth.

Two key lessons emerged from the Clayoquot Sound conflict that would have a profound impact on the GBR negotiations:

1. the effectiveness of market-based campaigns in changing an established incentive structure, and,

2. the ability of actors to develop collaborative solutions in spite of seemingly irreconcilable differences.

Clayoquot Sound signified a fundamental shift in the efficacy of environmentalism in B.C., representing a turning point in the ability of the environmental coalition to thrust its problem-solution narrative not only into the sovereign political space, but also onto the global political stage.

During the late 1990s, the Land and Resource Management Planning (LRMP) process was the B.C. government’s primary institutional strategy for minimizing land-use conflict and the primary mechanism for forest land-use planning in the province. In July 1996, the Central Coast Land and Coastal Resource Management Plan (CCLCRMP) was initiated to deliver recommendations on the use and management of Crown lands in the GBR region, including land-use zones and protected areas (British Columbia, 1996).

Government took the position that it could not halt resource development completely in the GBR during the planning process because this would result in serious social and economic disruption for communities inside and outside the region.

The only viable solution, environmentalists argued, was a moratorium on logging in all sensitive watersheds until all parties could agree on a comprehensive land use strategy for the region.

Environmental Coalition Takes Market Action

Eventually frustrated with the “talk and log” tactics of the forest companies and the provincial government and the lack of results from public opinion campaigns, the environmental coalition shifted venues by:

1) strengthening connections with international environmental advocacy networks, and

2) renewing commitments to market action in the USA and Europe aimed at targeting large consumers of BC’s old growth.

Efforts to politicize the “chain of consumption” proved effective, particularly since the boycott threats alone were enough to convince most companies to change their purchasing behavior out of fears of consumer protest and loss of market share (Shaw, 2004:379).

The stakes for forest companies operating on the BC coast were immense, with many hundreds of millions of dollars in sales in jeopardy unless forest companies could broker a deal with environmental groups to end the conflicts.

For example, in 1998, B&Q, the largest home improvement chain in the UK, decided to phase-out purchases of BC hemlock. In total, three European companies cancelled contracts worth about $7.5 million. In 1999, IKEA, with annual sales worldwide of $8 billion, announced that it would completely phase out old growth wood products by 2001. During 1999 and 2000 the three largest home improvement retailers in the USA – Home Depot, Lowe’s and Menards – all announced that they would stop purchasing products from old growth forests, to be followed shortly by others, including Wickes Inc, HomeBase Inc., and Centex Corp (Stanbury, 2000 197). In addition, sales of over $600 million per year in Germany alone where in jeopardy prior to signing of the GBRA.

By 1999, BC forest companies were losing millions of dollars in contracts because of the market boycotts in the US and Europe. International public relations campaigns by industry and government were proving ineffective and the development coalition could no longer control policy outcomes in its favour. At the same time, the formal LRMP process was “having difficulty reaching agreement and achieving tangible outcomes for all of the different groups involved” (CFCI, n.d.).

Formation of a Negotiating Group – CFCI

A number of forest companies decided that the only option, given mounting economic losses, entailed direct negotiations with the environmental groups outside of the formal government decision-making framework. In 1999, four large forest companies holding tenures in the GBR began to meet and formed a negotiating group called the Coast Forest Conservation Initiative (CFCI), opening the policy domain to new ideas.

The relationship between the BC government and CFCI was strained, since government faced the problem that CFCI represented only two of the interests involved: forest industry and environmentalists.

First Nations had invested much effort in government-to-government treaty negotiations linked to the formal LRMP planning process and refused to participate in an informal process without such links. Government was firm in its position that the responsibility for land use decisions rested with the government of British Columbia and First Nations.

Meanwhile the formal LRMP process designed to include all of the stakeholders in the region had made little progress after three years, largely because it had not adequately addressed the problem of First Nations land claims. Above all, government was not open at the time to truly creative solutions, largely because of the structural inertia and “path dependence” of past policy choices and the legitimacy trap if its IRM discourse (Wilson, 1998).

Formation of the Joint Solutions Project

In spite of many setbacks, CFCI companies and environmental groups formalized their discussions by establishing the Joint Solutions Project (JSP) to explore ways to end the market-based conflict over the forests in the GBR by collaborated on integrative solutions and developing a new vision for forest management on the coast.

Active participation by the First Nations in the Turning Point process (David Suzuki Foundation, n.d.), shifted the discussions to a new level where the provincial government had no option but to engage with the CFCI/JSP/Turning Point collaborative.

Agreement Forged Between Environmentalists and Industry

In July 2000, an agreement was forged between forest companies and environmental groups, whereby environmental groups agreed to halt their market campaigns in return for a promise from Weyerhaeuser and Western Forest Products not to log in 30 sensitive watersheds.

The draft agreement was presented to government as a realistic solution to resolving the conflict. The initial response from government, particularly the forests ministry, was disbelief concerning the amount of potential protected area on the map.

Government officials generally held the view that the formal multi-stakeholder LRMP planning process had been hijacked by the narrow special interests of the environmental groups who had successfully coerced forest companies into negotiation through economic extortion.

Because of the shift in incentive structure represented by the new economic realities, the forest companies involved were committed to achieving and implementing an agreement, almost regardless of government’s position. In their view, there was simply no other choice; they would stop logging if necessary, since they could not continue to operate at a financial loss.

At the same time, government also began to recognize the need to bring the ‘outsiders’ back to the LRMP table, or at least appear to do so. The most difficult challenge was to integrate the draft agreement and its radical solutions with the interests and demands of other participants in the Central Coast LCRMP process.

Government Forced to Catch Up and Face New Realities

In the end, government was forced to revise provincial statutes to accommodate the conditions of the logging moratorium.

Much of the resulting GBR framework agreement built on the principles and processes created and articulated by the JSP, in consultation with a wide range of individuals and organisations. The April 4th 2001 GBRA announcement by the provincial government represents a consensus agreement among all the parties involved at the CCLCRMP table.

It was in the best interests of all parties involved to demonstrate support for the consensus agreement, even though the outcome was distasteful to some.

Government sought to increase its credibility by proclaiming leadership in negotiating a truce and members of the JSP needed the legitimacy of government endorsement “to counter accusations that their process had been undemocratic and unrepresentative” (Shaw, 2004:382). In the end, self-interests became aligned with mutual interests.

This analysis shows that new actors became engaged in the GBR policy arena in the form of environmental groups (FAN, CRN, RAN), transnational ENGOs such as Greenpeace Germany and Greenpeace UK, and, importantly, the new cross-coalition collaborative alliances such as the CFCI and JSP.

The new ideas introduced by transnational knowledge networks proved particularly influential in the discursive shift that occurred with the GBRA (Bernstein & Cashore, 2000). These involved ideas related to “leverage politics,” including market-based tactics and strategies involving boycott campaigns and threats of economic reprisals, as well as ideas involving innovations in civic engagement, consensual discourse and collaborative strategies (for example, see Dodge, 2001; Webster, 2002).

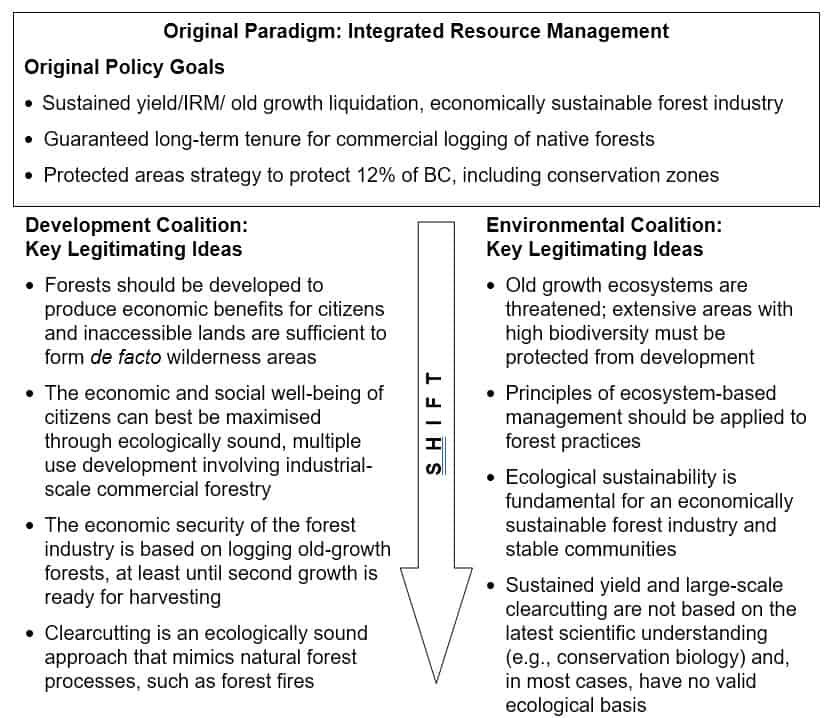

Paradigm Shift in Forest Policy

An important transition in the discursive shift occurred when participants in the JSP collaborative coalition achieved a draft consensus agreement on a set of principled ideas after having struggled to develop a solution that integrated shared ecological and economic interests and values.

The figure below depicts the discursive shifts that occurred in this policy subsystem.

GBR Policy Regime – Paradigm Shift in Ideas and Policy Goals

Lertzman et al. (1996:147) demonstrate that the paradigm shift in BC forest policy was based on the recognition that “commodity production under increasingly stringent Integrated Resource Management constraints is both inefficient as a way of allocating land between competing uses and ineffective in sustaining the full range of ecological services…”

Consequently the policy goals within the GBR shifted from commodity production within what was referred to as an Integrated Resource Management (IRM) framework “towards maintaining healthy forest ecosystems, turning commodity production levels such as AAC [Allowable Annual Cut] from an input into an output of the forest planning process” (1996:147).

Milestones in Protecting the Great Bear Rainforest

1996 – Land and resource management planning begins on B.C.’s coast.

2000 – Several coastal forest companies and environmental groups agree to collaborate through a Joint Solutions Project.

2003/2004 – Planning participants deliver consensus recommendations to the B.C. government; discussions begin with the First Nations.

2006 – Province of B.C. and the First Nations announce the Coast Land Use Decision and commit to ecosystem-based management throughout the Great Bear Rainforest.

2007 – New legal land use orders are established for the South Central Coast and Central North Coast.

2009 – B.C. government amends the land use orders to protect 50% of natural historic old growth forests; all participants agree to a five-year work plan to implement ecosystem based management.

2009 – 114 conservancies and 21 biodiversity, mining and tourism areas are established from 2006 to 2009.

2010/2011 – B.C. government reaches reconciliation protocol agreements with Coastal First Nations and Nanwakolas Council. One outcome is to increase their participation in the forest sector and protect cultural and social interests.

2014 – Joint Solutions Project submits detailed recommendations to B.C. government, Coastal First Nations and Nanwakolas Council.

2015 – the B.C. government invites public comments on a new proposed Great Bear Rainforest land use order and potential new Biodiversity, Mining and Tourism Areas.

2016 – the B.C. government enacts the new Great Bear Rainforest Land Use Order and the Great Bear Rainforest (Forest Management) Act to legally implement elements of the announcement.

Case Study: South East Queensland Forest Agreement

Queensland, Australia

In September 1999, the government of Queensland (Australia), key conservation groups, and the Queensland Timber Board (QTB) entered into a written agreement that changed the course of natural resource management policy in the state. The South East Queensland Forests Stakeholder/Government Agreement, signed 16 September 1999.

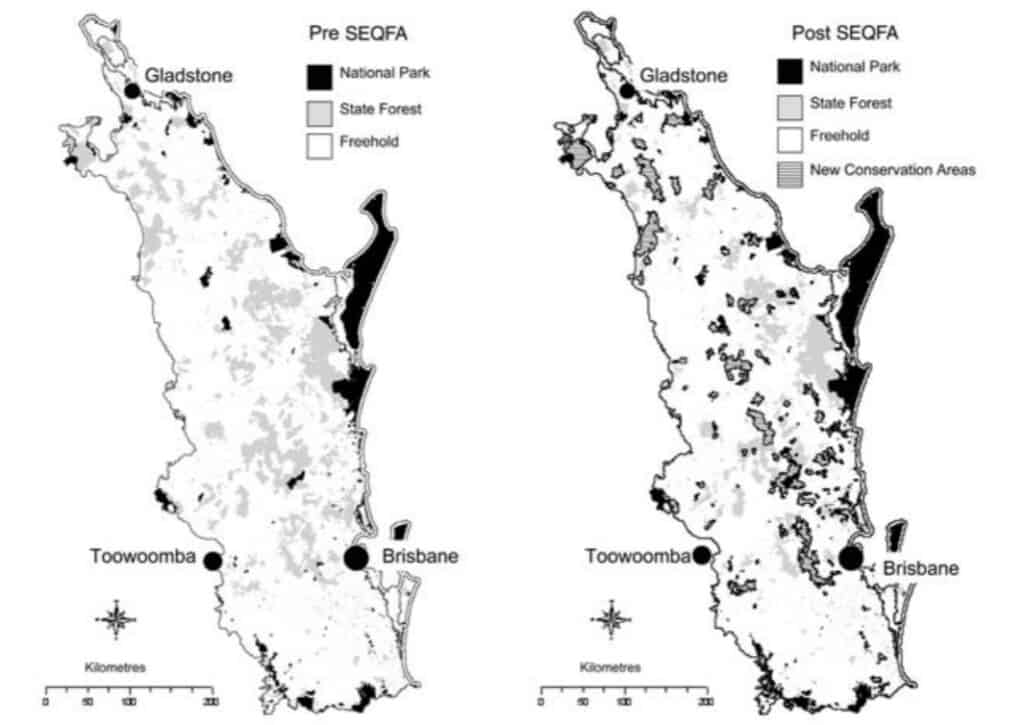

The SEQ Forest Agreement (SEQFA) represents the successful resolution of complex social and environmental issues, in particular, the allocation and tenure of approximately 689,000 hectares of public native forest with high conservation value as well as high suitability for commercial forestry.

Confrontations over Native Forests Became Intractable During 1990s

The story of the SEQFA is one of competing coalitions successfully breaking out of structured conflict over the native forests of the SEQ to collaborate on renegotiating the resource regime. Confrontations over the native forests grew intractable in the 1990s as forest industry sought to increase production at the same time as conservation groups mobilized to protect biodiversity and prevent further loss of irreplaceable habitat.

The forces at work in the SEQFA policy domain included economic adjustment, civic engagement, and a strengthening biodiversity and sustainability discourse. This is also the story of government incapacity and institutional failure in establishing a policy context capable of integrating the level of innovation needed to resolve the impasse.

With much of the conduct of the SEQFA and the context of the Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) policy process already well-described by Brown (2001; 2002b), McDonald (1999), and Clarke (Unpublished 2000), this article focuses primarily on the discursive practices and collaborative processes involved in achieving integrated, sustainable policy solutions.

Complex Realities of Land Use in South East Queensland

The SEQ region encompasses about 6.1 million hectares in the South Eastern corner of Queensland, with about 45 per cent covered in forest. About 55 per cent of the native vegetation has been cleared for urban development and agriculture. The forest industry in Queensland in the early 2000s contributed approximately $1.7 billion to the state economy and directly employed around 17,000 people (Queensland, 2004).

In Australia, conflict over the remnant forests kept the conservation of native forest ecosystems on the political agenda for several decades. In 1992, the National Forest Policy Statement (NFPS) was signed by the States and Commonwealth to provide an intergovernmental policy framework for the management of Australia’s forests.

Government Attempts to Resolve Forest Management Conflicts

Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) represented the means by which the principles and objectives of the NFPS were to be implemented. RFAs were 20-year agreements between the Commonwealth and State governments designed to resolve the conflicts over forest management by providing a balance between environmental, social, economic and heritage values.

By the late 1990s, the Queensland forest industry faced severe challenges, the main issue being certainty of access to timber. The yield for sawlogs on public forest land declined by 50 per cent from the 1970s to 2000 while the total cut from native forests and plantations increased during that time. The industry had been making a quiet transition from native forests to plantations, consistent with national trends, while focusing on native forests and almost ignoring the role of plantation resources (Brown, 2002a:22).

In early 1997, an RFA ‘scoping’ agreement was signed between Prime Minister Howard and Queensland Premier Beattie, identifying the boundaries, broad objectives, and the legal and policy obligations of both governments. A scientific bioregional assessment confirmed the difficulty of achieving both a comprehensive forest reserve to protect biodiversity and a native forest logging industry.

Federal Government Attempts to Contain Forces Beyond its Control

The RFA process became highly politicized as the federal government pursued its political agenda of a forest industry based on continued logging of native forests in perpetuity and chose to intervene in the process, as it had with RFAs in other states.

Commonwealth and Queensland government officials took control of the process and excluded the reference panel from meetings as the forest management options were developed.

By late-1998, the structural deficits of the formal Commonwealth-State RFA process had become apparent to key stakeholders, as well as many knowledgeable observers and concerned public, with a growing realisation that the status quo was simply unacceptable.

Conservationists, the timber industry and key State agencies became increasingly dissatisfied with the command-and-control Commonwealth approach and the incapacity of the RFA process to accommodate innovative solutions.

Queensland Government Offers an Alternative Process

In July 1999, in the face of intractable conflict Queensland Premier Beattie stepped in to play the role of policy broker, committing State government resources to supporting the process with or without Commonwealth government support. As a result, competing coalitions undertook direct negotiations outside the RFA framework, a move welcomed by the Premier and affiliates within State government who were determined to end the politically damaging conflict, and viewed with alarm by the ‘conservative’ faction within the Commonwealth and State governments and forest industry.

Contrary to the expected outcome for an RFA – a typical compromise solution carving a contentious area into various conservation and development zones – the SEQ stakeholders chose to think outside of the “spatial” box and opted for an innovative transitional solution that introduced a temporal element to the policy discourse.

The collaborative coalition successfully developed a shared vision for new outcomes, devised the technical solutions necessary for implementation, and communicated the new direction to a diversity of stakeholders in such a way as to gain their support.

Recalcitrant State government officials and agencies found themselves compelled to support the new vision, even though the Commonwealth continued to attempt containment of the discourse within the old RFA/ multiple use framework.

Stakeholders Collaborate to Create Innovative Solutions

On 16 September 1999, the Queensland government, QTB and key conservation groups signed the SEQ stakeholder forest agreement (Queensland, 1999).

Stepping outside of the constraints of the RFA process, the stakeholder solution comes close to meeting the national reserve criteria (JANIS, 1997) by immediately protecting 425,000 ha (62% of the area) of high conservation value forests, with continued logging on 184,000 ha (26%) to be phased-out over 25 years, and future management options to be decided on 80,000 ha (12%).

The key concept underlying the success of the agreement was the provision for the timber industry to make a complete transition from native-forests to a plantation-based resource by 2025. This innovative, integrated solution addresses the interests and objectives of both environmental and development coalitions, in contrast to the typical RFA approach advocated by the Commonwealth and implemented in the other States.

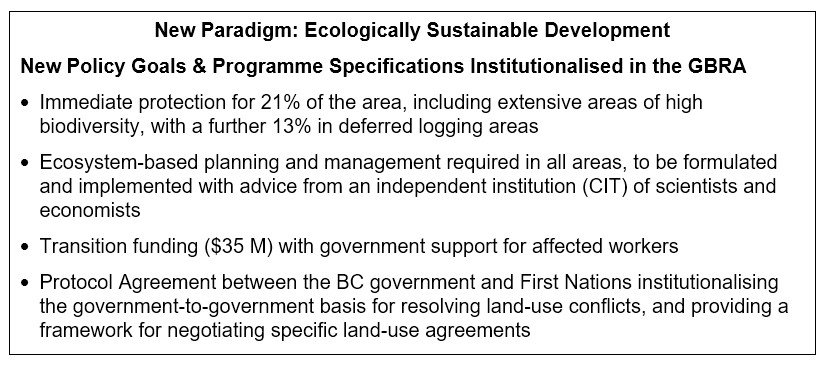

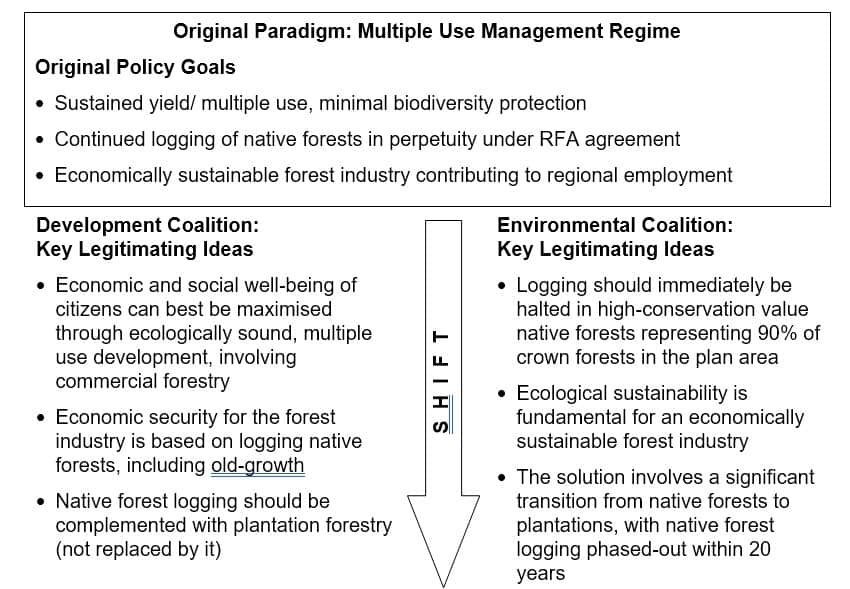

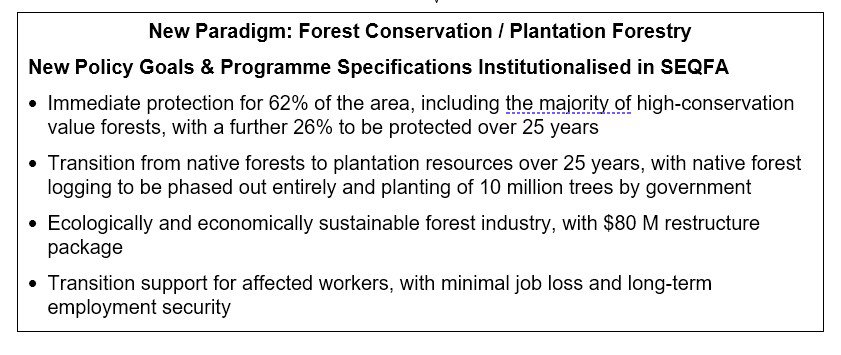

The figure below depicts the discursive shifts that occurred in this policy subsystem by comparing two sets of interdependent factors:

- the original policy goals and the new policy goals institutionalized through the SEQFA, and

- the key legitimating ideas prominent in the parallel discourses of the two competing coalitions prior to the consensus discourse that emerged.

The figure also shows the original alignment between the multiple use policy goals and the dominant discourse of the development coalition, and the subsequent alignment between the collaborative discourse, integrating the ecological sustainability ideas of the environmental coalition, and the new collaborative policy goals.

SEQ Policy Regime – Paradigm Shift in Ideas and Policy Goals

Collaborative Governance Can Lead to Innovative Solutions

Collaborative governance is one expression of the robust emergence of deliberative democracy in the modern era. Within this context, the unfolding role of civil society promises to exert a strong influence on the continuing redefinition of liberal democracy. Societal actors are playing increasingly prominent roles in facilitating the renegotiation of resource regimes and assisting with the development of integrated solutions for economic and ecological sustainability.

Long-term solutions to intractable conflicts are elusive, particularly in value-driven disputes. Successful renegotiation of resource regimes relies on the parties involved designing their own solutions including the development of appropriate policy goals. For this to occur, state actors must yield significant control to collaborative participants where appropriate and must be prepared to implement innovative solutions that could entail institutional redesign or transformation.

There are no easy solutions to the quandaries faced by governments with respect to maintaining the legitimacy of a representative democracy while maximizing the benefits of participatory governance, especially given the dangers of powerful players hijacking the public interest.

Nevertheless, in hindsight it becomes apparent that even innovative land-use planning initiatives, such as Australia’s RFA process and British Columbia’s CORE “shared decision-making” model and LRMP processes, proved inadequate for integrating recently legitimated values. This is largely because politicians and policy-makers in both cases attempted to contain decision-making negotiations within the confines of established policy frameworks and top-down policy goals, in spite of the paradigm shift in progress.

In value-driven conflicts, policy goals are often at the heart of contention and state-imposed solutions at the technical, instrument level simply will not suffice.

The collaborative governance evident in the cases represents a positive response to the inadequacy of corporatist and pluralist systems in implementing sustainability goals.

Collaborative governance is not a likely option where the incentive structure precludes involvement by powerful actors determined to maintain the status quo. However, in those situations where the incentive structures shift significantly, in response to cognitive or non-cognitive influences, collaboration between long-standing adversaries becomes a viable, if not preferred, alternative.

By forming collaborative coalitions, one-time adversaries in these cases gain the capacity to develop creative, integrative solutions with the potential to penetrate and expand the cognitive boundaries of “accepted” policy discourse.

Where empowered by public consent, such coalitions can legitimately compel governments and powerful interests to renegotiate contested resource regimes in the “shadow of collaboration,” improving society’s response to long-term sustainability challenges

About the Author

George Sranko is a founding director of Wise Democracy Victoria and an associate with the international Center for Wise Democracy. He has an MA (Hons) in Professional Ethics and Governance from Griffith University, Queensland, Australia and a B.Sc. in Zoology from the University of British Columbia, Canada.

George has spent over thirty years as an environmental educator, activist and professional biologist. He was one of the original appointees to the Provincial Capital Commission Greenways Committee in Victoria, BC in the early 1990s and was instrumental in the collaborative efforts involved in creating one of the most successful greenways networks in Canada.

He has consulted extensively with all levels of government on a range of resource management projects involving strategic planning, development, and implementation of programs and policies. As an environmental activist he has come to realize that ecological sustainability is ultimately in the hands of citizens; and in particular those individuals and groups who are willing to take bold and radical steps aimed at shifting paradigms and creating systemic change.

All too often, politicians and decision-makers remain mired in the status quo and captive to entrenched interests, to the degree that sufficiently innovative solutions must come from outside the system. Not satisfied with theoretical discussions about collaborative processes, George is a trained dynamic facilitator, an approach proven to engender breakthrough results.

References

Alper, D.K. & Salazar, D.J. (2000) Sustaining the forests of the Pacific Coast: forging truces in the war in the woods UBC Press, Vancouver.

Arnstein, S. (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, 216-224.

Bartlett, T. (1999) Regional Forest Agreements — a Policy, Legislative and Planning Framework to achieve Sustainable Forest Management in Australia. Environmental and Planning Law Journal, 16, 328-38.

Bernstein, S. & Cashore, B. (2000) Globalization, Four Paths of Internationalization and Domestic Policy Change: The Case of EcoForestry in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 33, 67-100.

Booher, D.E. & Innes, J.E. (2001). Network Power in Collaborative Planning. Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California at Berkeley.

Britell, J. (1997) The Myth of “Win-Win”.

British Columbia (1996). News Release. Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management, Victoria, BC.

Brown, A. (2002a) ‘Collaborative governance versus constitutional politics: decision rules for sustainability from Australia’s South East Queensland Forests Agreement’. Environment Science & Policy, Volume 5, 19-32.

Brown, A.J. (2001) Beyond Public Native Forest Logging: National Forest Policy and Regional Forest Agreements After South East Queensland. Environmental and Planning Law Journal, 18, 189-210.

Brown, A.J. (2002b) Collaborative governance versus constitutional politics: decision rules for sustainability from Australia’s South East Queensland Forest Agreement. Environmental Science & Policy, vol 5, 19-32.

Burrows, M. (2000). Multistakeholder Processes: Activist Containment versus Grassroots Mobilization. In Sustaining the forests of the Pacific Coast: forging truces in the war in the woods (ed D.K. Alper). UBC Press, Vancouver.

CFCI (n.d.) New Thinking About Forest Conservation. Coast Forest Conservation Initiative.

Clarke, P. (Unpublished 2000). The South-East Queensland Forest Agreement: Conflict and Collaboration in Regional Resource Management. Griffith University, Environmental Science/Law Research Project, Brisbane.

Cohen, J.L. & Arato, A. (1992) Civil society and political theory MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Cortner, H. & Moote, M. (1994). Setting the Political Agenda: Paradigmatic Shifts in Land and Water Policy. In Environmental policy and biodiversity (ed R.E. Grumbine). Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Culpepper, P.D. (2002) The Political Perils of Collaborative Governance in France and Italy. In Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Aug 28 – Sept 1, Boston, MA.

Daniels, S.E. & Walker, G.B. (2001) Working through environmental conflict: the collaborative learning approach Praeger, Westport, Conn.

Dargavel, J. (1998) Politics, Policy and Process in the Forests. Australian Journal of Environmental Management, 5, 25-30.

David Suzuki Foundation (n.d.) Turning Point Backgrounder, Vancouver, BC.

Dodge, W. (2001). The Triumph of the Commons: Governing 21st Century Regions, Rep. No. 4 Monograph Series. Alliance for Regional Stewardship, Denver.

Dorcey, A.H.J. & McDaniels, T. (2001). Great Expectations, Mixed Results: Trends in Citizen Involvement in Canadian Environmental Governance. In Governing the Environment (ed E. Parson). University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Dryzek, J.S. (1996) Political inclusion and the dynamics of democratization. American Political Science Review, 90, 475-487.

Dryzek, J.S. (2001) Legitimacy and Economy in Deliberative Democracy. Political Theory, 29, 651-669.

Duffy, D., Hallgren, L., Parker, Z., Penrose, R., & Roseland, M. (1998). Improving the Shared Decision-Making Model: An Evaluation of Public Participation in Land and Resource Management Planning (LRMP) in British Columbia, Summary Report. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC.

Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (1997) Getting to yes : negotiating an agreement without giving in, 2nd ed edn. Arrow Business Books, London.

Forsyth, J. (1998) Anarchy in the Forests: a Plethora of Rules, an Absence of Enforceability. Environmental and Planning Law Journal, 15, 338-49.

Freeman, J. (1997) Collaborative Governance In The Administrative State. UCLA Law Review, 45, 1-98.

Goldstein, J. & Keohane, R.O. (1993). Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytic Framework. In Ideas and foreign policy : beliefs, institutions, and political change (eds J. Goldstein & R.O. Keohane). Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Goodin, R.E. (2003) Democratic Accountability: The Third Sector and All. In Conference on ‘Crisis of Governance: The Nonprofit/Non-Governmental Sector’, Hauser Center for Non-Profit Organizations, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Hall, P.A. (1993) Policy Paradigms, Social Learning and the State: The Case of Economic Policy Making in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25, 275-96.

Hoberg, G. (2001). Policy Cycles and Policy Regimes: A Framework for Studying Policy Change. In In Search of Sustainability: British Columbia Forest Policy in the 1990s (eds B. Cashore, G. Hoberg, M. Howlett, J. Rayner & J. Wilson). UBC Press, Vancouver.

Howlett, M. (1994) Policy Paradigms and Policy Change: Lessons from the Old and New Canadian Policies towards Aboriginal Peoples. Policy Studies Journal, 22, 631-51.

Howlett, M. (2001). Complex Network Management and the Governance of the Environment: Prospects for Policy Change and Policy Stability Over the Long Term. In Governing the environment : persistent challenges, uncertain innovations (ed E. Parson), pp. xii, 430 p. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Howlett, M. (2002) Do Networks Matter? Linking Policy Network Structure to Policy Outcomes: Evidence from Four Canadian Policy Sectors 1990-2000. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 35, 235-267.

Howlett, M. & Ramesh, M. (1995) Studying public policy: policy cycles and policy subsystems Oxford University Press, Toronto ; New York.

JANIS (1997). Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia. Report by the Joint Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council (ANZECC) – Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries and Agriculture (MCFAA) National Forest Policy Statement Implementation Subcommittee, Canberra.

Keck, M.E. & Sikkink, K. (1998) Activists beyond borders : advocacy networks in international politics Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Keeley, J. & Scoones, I. (2003) Understanding environmental policy processes : cases from Africa Earthscan, London ; Sterling, VA.

Kissling-Näf, I. & Varone, F. (2000) Historical Analysis of Institutional Resource Regimes in Switzerland. A Comparison of the Cases of Forest, Water, Soil, Air and Landscape. In 8th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP); “Crafting Sustainable Commons in the New Millennium”, Bloomington.

Krugman, P.R. (1994) Peddling prosperity: economic sense and nonsense in the age of diminished expectations W.W. Norton, New York.

Lasker, R.D. & Weiss, E.S. (2003) Broadening Participation in Community Problem Solving: a Multidisciplinary Model to Support Collaborative Practice and Research. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Vol.80.

Lertzman, K., Rayner, J., & Wilson, J. (1996) On the Place of Ideas: A Reply to George Hoberg. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 29, 145-148.

Lewicki, R. & Robinson, R. (1998) Ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 665-682.

Lewicki, R.J., Saunders, D.M., & Minton, J.W. (1999) Negotiation, 3rd ed edn. Irwin/McGraw-Hill, Boston.

Lewicki, R.J., Saunders, D.M., & Minton, J.W. (2001) Essentials of negotiation, 2nd edn. Irwin/McGraw-Hill, Boston, Mass.

Libecap, G.D. (1989) Contracting for Property Rights Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lipschutz, R.D. & Mayer, J. (1996) Global civil society and global environmental governance: the politics of nature from place to planet State University of New York Press, Albany.

Litfin, K. (1994) Ozone discourses : science and politics in global environmental cooperation Columbia University Press, New York.

Magnusson, W. & Shaw, K., eds. (2003) A Political Space: Reading the Global through Clayoquot Sound. University of Minnesota Press.

Mason, M. (1999) Environmental democracy St. Martin’s Press, New York.

McDonald, J. (1999) Integrated Environmental Management – A Whole-of-Government Responsibility? In 18th Annual National Environmental Law Conference. (ed N.E.L. Assoc), Sydney, 8-10 Sept 1999.

Morishita, S. & Hoberg, G. (2001) The Great Bear Rainforest: Peace in the Woods? University of British Columbia.

Munton, R. (2003). Deliberative democracy and environmental decision-making. In Negotiating environmental change : new perspectives from social science (ed I. Scoones), pp. 109-136. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA.

Neumann, R. (1992). Resolving Environmental Disputes in the Public Interest – An Overview. In Resolving Environmental Disputes in the Public Interest (ed R. Neumann). Environmental Inst. of Australia (SEQ Div), Brisbane.

Norman P., Smith, G., McAlpine C.A., and Borsboom A. (2004). South-East Queensland Forest Agreement : Conservation outcomes for forest fauna. In book: Conservation of Australia’s Forest Fauna (pp.208-221) Publisher: Royal Zoological Society of NSW, Mosman, NSW. Editors: D. Lunney, January 2004. DOI: 10.7882/FS.2004.015

Papadakis, E. & Young, L. (2000). Mediating clashing values: environmental policy. In The Future of Governance: Policy Choices (ed M. Keating). Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, NSW.

Queensland (1999). South East Queensland Forest Agreement (SEQFA), Brisbane.

Queensland (2004). An overview of the Queensland forest industry: the economic and social importance of forestry. Department of Primary Industries.

Rein, M. & Schön, D. (1993). Reframing Policy Discourse. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (ed J. Forester). Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Renn, O., Webler, T., Rakel, D., Dienel, P., & Johnson, B. (1993) Public Participation in Decision Making: A Three Step Procedure. Policy Sciences, 23, 189-214.

Renn, O., Webler, T., & Wiedemann, P.M. (1995) Fairness and competence in citizen participation : evaluating models for environmental discourse Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht ; Boston.

Rhodes, R.A.W. (1997) Understanding governance : policy networks, governance, reflexivity, and accountability Open University Press, Buckingham ; Philadephia.

Salamon, L.M. (2002). The New Governance and the Tools of Public Action, an Introduction. In The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance (ed O.V. Elliott). Oxford University Press, New York.

Scharpf, F.W. (1993) Positive und negative Koordination in Verhandlungssystemen. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 24, 57-83.

Shaw, K. (2004) The Global/Local Politics of the Great Bear Rainforest. Environmental Politics, 13, 373-392.

Stanbury, W.T. (2000) Environmental groups and the international conflict over the forests of British Columbia, 1990 to 2000 SFU-UBC Centre for the Study of Government and Business, Vancouver.

TCMWG (n.d.) Website. Trout Creek Mountain Working Group (Oregon, USA).

Thomas, J.C. (1993) Public Involvement and Governmental Effectiveness: A Decision-making Model for Public Managers. Administrative Science and Society, 24, 444-69.

Tuckey, W. (2000). Media Release, Rep. No. AFFA00/14TU. Hon W Tuckey MP, Canberra.

Viehöver, W. (2000) Political Negotiation and Co-operation in the Shadow of Public Discourse: The Formation of the German Waste Management System DSD as a Case Study. European Environment, 10, 277-292.

Wainwright, H. (1994) Arguments for a new left : answering the free-market right Blackwell, Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA.

Webler, T. (1995). “Right” Discourse in Citizen Participation: An Evaluative Yardstick. In Fairness and competence in citizen participation : evaluating models for environmental discourse (ed P.M. Wiedemann), pp. xix, 381 p. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht ; Boston.

Webster, R. (2002) Greening Europe together: the collaborative strategies of the European environmental NGOs. In Paper prepared for Political Studies Association 52nd Annual Conference Making Politics Count, University of Aberdeen, 5 – 7 April 2002.

Wilson, J. (1998) Talk and log: wilderness politics in British Columbia, 1965-96 UBC Press, Vancouver.

Wilson, J. (2001). Experimentation on a Leash: Forest Land Use Planning in the 1990s. In In search of sustainability: British Columbia forest policy in the 1990s (eds B.W. Cashore, G. Hoberg, M. Howlett, J. Rayner & J. Wilson). UBC Press, Vancouver.

Winn, M. (2001) Building stakeholder theory with a decision modeling methodology. Business and Society, vol 40:2, 133-166.

Wondolleck, J.M. & Yaffee, S.L. (2000) Making collaboration work : lessons from innovation in natural resource management Island Press, Washington, D.C.