The lifespan of great white sharks is thought to be up to 70 years or more, which is far longer than earlier estimates. This makes it one of the longest-living cartilaginous fishes currently known. Scientists believe that female great white sharks need 33 years to attain reproductive age, while males reach sexual maturity in about 26 years.

Great white sharks give birth to live young, and the pups are born about 5 feet long (1.5 m). They are extremely skilled and intelligent hunters and often specialize in seals and other marine mammals, as well as larger fish. They can live in cool, temperate waters by being one of the few warm-blooded fish.

Great white sharks travel alone and can cover hundreds of miles of territory as they seek out and patrol seasonal food sources, such as seal colonies.

One of the most recognizable and notorious of sharks, the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), has been involved in more provoked and unprovoked attacks on humans than any other shark in history. (International Shark Attack File 2021).

Great White Shark Facts to Amaze Your Friends

- Great white sharks can smell blood in seawater at concentrations as low as one part per million.

- Their entire body is covered in tiny teeth called denticles, forming a suit of armor.

- They can detect a human heartbeat using tiny electrical impulses, like an ECG monitor.

- They can detect electrical impulses from any creature at close range as soon as it moves a muscle.

- They can detect and follow any creature that swims nearby because of vibrations in the water.

- Great whites are among the longest-lived species in the animal kingdom.

- The great white is one of the very few warm-blooded fish and can maintain core body temperatures higher than the surrounding waters.

- The first pups that hatch consume the remaining eggs or pups while they are still within their mother – a form of cannibalism known as oophagy.

- Great whites have killed more people than any other shark species with 59 fatal unprovoked attacks – of course this number represents all documented attacks ever recorded.

- Sharks are several hundred million years older than dinosaurs.

What is the Lifespan of the Great White Shark?

Great white sharks can live up to 70 years, giving them one of the longest lifespans in the animal kingdom.

In a study of great white sharks in the western Atlantic, males reached sexual maturity at 26 years of age and females at 33 years.

By way of comparison, the great hammerhead begins breeding at eight or nine years old and can live for thirty to forty years, while the tiger shark achieves sexual maturity at seven or eight years with a lifespan of roughly 30 years.

One reason great whites grow so slowly is that their intestines are small and tightly folded, which causes slower digestion and longer gaps between meals.

In females, a smaller intestine makes room for a large uterus, allowing her to carry her pups long enough for them to reach 5 feet (1.5 m) in length before birth.

According to one study, inexperienced, adolescent sharks with less expertise at catching seals roam over wide distances in search of prey concentrations. As they get older, sharks start to establish distinct territories by getting to know the intricacies of geography, currents, and the routes that seals frequent.

Great White Sharks Are Built for Speed

Sharks Have Teeth Over Their Entire Body

Sharks are built for speed; they move through the water with ease thanks to tooth-like features called denticles that line their skin.

At just a tenth of a millimeter long, these ridge-lined structures reduce drag by dissipating tiny eddies that form along the skin.

Rows of denticles also serve as tooth-hard body armor that protects against attacks from other sharks and prey fighting back. Rows and rows of these tiny teeth also provide a barrier against parasites.

The speed of the great white is further enhanced by several significant anatomical innovations including torpedo-shaped bodies powered by tail fins with long upper and lower lobes.

With lighter skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone, sharks have the flexibility to accelerate and change directions quickly.

White sharks have a triangular dorsal fin, a pointed snout, and a crescent-shaped caudal fin, giving them the classic shape of a shark.

They can be recognized by the abrupt color change on their sides, which goes from a very pale, almost white, underside to a top that is greyish black.

This species demonstrates sophisticated social activities and is known for its intelligence and inquisitiveness.

Are Great White Sharks Warm Blooded?

Yes, you can say that a great white shark is warm-blooded, but there are some nuances to consider. They can keep their core body temperature above the ambient seawater temperature, largely through their behaviors.

Most sharks in warm, tropical oceans have bodies that are the same temperature as the water around them. This helps them use energy as efficiently as possible. In cooler waters, however, digestion, muscular reactions, and even brain function slow down significantly.

Warm-blooded animals, or endotherms, have the capacity to generate heat metabolically, thereby maintaining a constant body temperature. This is a remarkable evolutionary characteristic, since creatures that can control their own temperature are far less subject to extreme thermal variations in their environment.

The great white is not a true endotherm, but you could call it partially warm-blooded. This means that the great white shark’s core body temperature is internally controlled but is not constant. If you want to be precise, you could say that the great white is an endothermic poikilotherm or mesotherm.

Animals that are poikilothermic have developed characteristic behaviors that help them regulate their own body temperature. (Most mammals can keep their core body temperatures relatively constant – homeotherms. One exception is the Naked Mole Rat – the only cold-blooded mammal!)

The great white shark is one of five species of shark that can recycle some of the heat generated by their muscles as they swim, thereby raising their internal body temperatures above the temperature of cold water. This enables these sharks to move more vigorously and continuously while living in colder waters. The other members of this family are the longfin mako (Isurus paucus), the shortfin mako (Isurus oxirynchus), the porbeagle (Lamna nasus), and the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis).

A great white shark can also maintain its body temperature by swimming in the sunshine near the surface and eating when its body temperature rises. This allows for improved digestion and a faster metabolism to maintain this condition because a white shark cannot afford to lose body heat to the water around it.

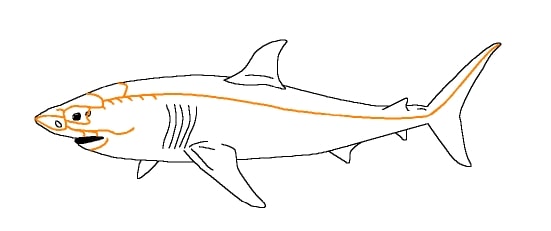

Most of the muscle in a typical shark’s body is white, which is used to power quick movements and acceleration.

![Illustration of the heat-generating muscles of lamnid sharks. [CREDIT: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation]](https://animalsfyi.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Shark-great-white-warm-blooded-mechanism-compressed-UFlorida-1024x646.jpg)

In laminid sharks like the mako or great white, however, a band of red muscle lines the core of the body, giving the shark endurance over long migrations. These red muscles are also surrounded by a web of veins and arteries known as rete mirabile.

The shark recycles the heat produced in the red muscle and sends it to vital body parts like the brain and eyes as it hunts seals and other large animals. The oxygen-depleted blood flows out of the muscle toward the gills, and the heat from metabolic activity is transferred to the oxygen-rich blood flowing in.

The huge red muscular masses on the sides of these five shark species are located more anteriorly, closer to their spines. As a result, their bodies can maintain their rigidity and keep the heat that their muscles produce when they contract. And as a result, internal body temperatures rise above those of the surroundings and can continue to do so even as sharks transition from warm surface waters to cooler, deep waters.

How Do Great White Sharks Retain Their Body Heat?

The “rete mirabile,” a Latin term that translates to “beautiful net,” is a configuration of densely branching blood arteries that allows heat to be retained.

Through the rete mirabile, arterial, oxygenated blood travels toward the muscles close to the body’s center while flowing counterclockwise to warm blood that is exiting the muscles. As the blood moves toward the swimming muscles after being oxygenated, it warms.

In order to prevent heat from being lost to the environment, the heat produced by the activity of swimming is recycled to remain within the muscles rather than traveling through the blood to the gills.

How Do Great White Sharks Hunt for Prey?

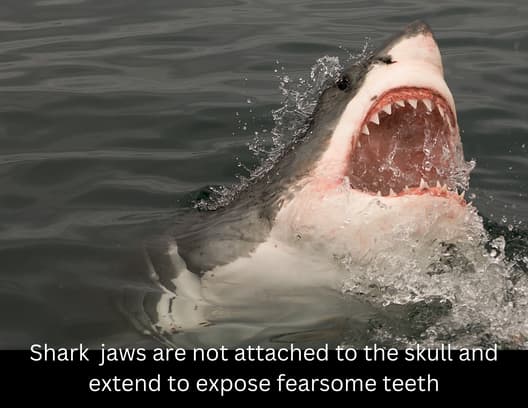

Predatory sharks seize their prey by lunging and extending their jaws out from the skull. They can accomplish this because their jaws are separate from their skulls, so they have the amazing ability to reach for the prey with their tooth-studded jaws!

White sharks frequently cruise past offshore reefs, banks, and shoals as well as rocky headlands where deep-water drop-offs are close to the shore. These areas are home to seals, sea lions, and walruses.

White sharks typically move purposefully around the water’s surface or just off the bottom, spending little time at midwater depths.

Large sharks like the great white and the tiger shark utilize their sharp teeth to rip their food apart with savage side-to-side motions.

Since their teeth are easily broken or shattered, sharks regularly produce new rows of teeth that roll toward the front of their jaws to replace them.

A series of large fins along their sides, top, and bottom stabilize the shark’s swimming motion.

A white shark leaping out of the water with its kill is one of the most dramatic natural spectacles that draws tourists from all over the world.

In the waters surrounding South Africa, the arctic ocean’s chilly, nutrient-rich waters are drawn close to the coast by strong ocean currents, which feed an explosion of marine life.

Just off Haute Bay Harbor, one of the larger islands is known as Seal Island.

It’s remoteness from the land and the rough underwater environment make it the perfect haven for seals.

There are hundreds of Cape fur seals – along with the great white sharks that feed on them.

The seals spend most of the year feeding offshore, consuming schooling fish like sardines, anchovies, and mackerel as well as seabirds and even penguins as summer approaches.

The Amazing Sensory Abilities of Great White Sharks

Like other sharks, the great white is a marvel of highly integrated sensory and motor abilities in the often-murky medium of the ocean.

Basically, a shark can detect and home in on any living creature that enters its underwater domain. I always like to entertain audiences by letting them know that the best way to become part of the food chain is to simply enter the ocean!

The great white shark understands its world through an acute sense of smell; it is said to be able to detect one part per million of blood in seawater. This allows the great white to identify and track prey long before they become visible.

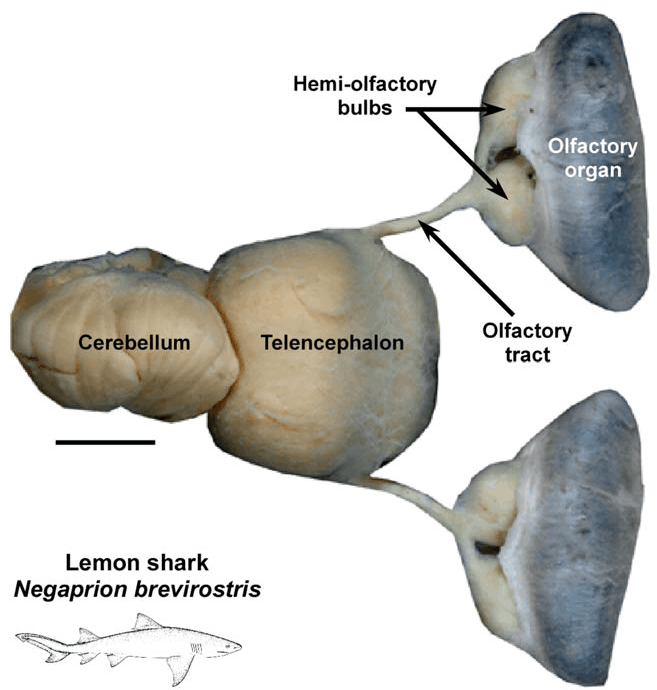

The great white shark has one of the largest olfactory systems found in any ocean creature. It has two large bulbs nestled in its snout, which are connected to a massive frontal brain and two large optical lobes behind it.

Once the prey is spotted, the white shark becomes a visual hunter, decoding the interplay of shapes and shadows ahead. It locks in on its prey from a distance and frequently rises out of the water to get a better look or to take a test bite.

A mature great white shark’s brain is approximately two feet long and extends to the brain stem at the top of the spinal column.

The brain integrates a variety of sensory apparatus tuned to the highly conductive properties of the ocean, including tiny pores arranged along its snout. These pores open into a series of jelly-filled pockets known as ampullae of Lorenzini.

Specialized nerve cells associated with these ampullae can read the voltage flowing into each pore, allowing a shark to detect minute electric currents in the water. This means that as soon as an animal moves a muscle, a nearby shark can detect the electric current produced. A beating heart is a moving muscle, and a shark can detect a beating heart even in murky water.

Sharks can detect vibrations in the water with their inner ear as well as with the lateral line, a sensory system that runs the length of their bodies. Any movement in the water would create pressure differences that a shark would be able to detect and follow.

When a shark follows an odor trail left by prey, it may use its lateral line to focus on vibrations produced by the swimming motions of the prey. Vibrations pass into fluid-filled canals where they excite air-like cells. These cells move and sway with the vibrations, transmitting the information to the brain.

Lifecycle of the Great White Shark

Great white sharks are ovoviviparous, which means the eggs hatch inside the female womb and the mother shark gives birth to live young after they hatch. The ones that hatch are the lucky ones! They get to feed on the unhatched eggs inside the womb!

The gestation period of the great white is thought to be 12 to 18 months.

Within the first month, the shark pup’s formidable jaws start to take shape.

Great whites engage in a form of cannibalism known as oophagy. When the first pups hatch, they consume the remaining eggs or pups while they are still within their mother. Talk about being born in a competitive environment!

Live births happen in the spring and summer, and the highest number of pups recorded is 14, from a mother measuring 15 feet (4.5 m) that was accidentally killed off Taiwan in 2019.

Sharks generally do not care for their young. As soon as the pups are born, they swim away and care for themselves. If they are smart, they’ll swim fast because mom is probably hungry!

As giant apex predators, great whites have little to fear from most other animals. They are at the top of the food chain in most of the waters they frequent.

There is one predator, however, that the sharks are learning to fear more and more… Orcas or Killer Whales. It appears that in some oceans, particularly off South Africa, orcas have acquired a taste for the liver of great white sharks. Since the sharks usually travel alone, they don’t stand much of a chance if they encounter a pack of orcas on the hunt.

The typical defense pattern for the shark is to swim in tight circles, which might work against a lone hunter but has not very effective when confronted by a pack of hungry orcas.

Video of Orcas Killing Great White shark for its liver

What Role Do Sharks Play in the Ecosystem?

Sharks play an important role in maintaining the balance of ocean ecosystems.

Sharks are the apex predators in many marine ecosystems, which means they have few natural predators and eat creatures lower on the food chain.

Through fear, sharks influence the behavior and distribution of their prey species. The entire ecosystem may be impacted by this indirect control over prey species.

Sharks help to protect seagrass meadows

For example, sharks deter their prey, sea turtles, which consume seagrass, thereby helping to protect seagrass meadows. When sharks are present the turtles keep moving, grazing across a wide area of seagrass without overgrazing a single location.

Without sharks, the seagrass meadows, which are crucial habitats for a variety of fish, shellfish, and birds, can become swiftly destroyed by the turtles’ heavy grazing.

Sharks have an important role to play in protecting coral reefs.

According to recent studies, shark protection may also be advantageous for coral reefs.

It has been demonstrated that the removal of sharks from coral reef ecosystems causes a rise in the mid-range predators that feed on herbivorous fish. As the meso-predators increase in numbers, the herbivore numbers decrease.

With fewer herbivores eating the algae, out-of-control algae can swiftly cover and smother an entire coral reef.

This change from a coral to algae-dominated reef diminishes biodiversity and weakens the reef’s resistance to natural disasters like coral bleaching and storms.

How do Great White Sharks Fit into the Shark Lineage?

The great white shark’s size sets it apart from all other predatory sharks. Adults can reach lengths of over 6 meters and weights of as least a ton.

The white shark and mako are both members of the Lamnidae or mackerel shark family, which includes large, swift sharks that can be found in oceans all over the world.

They are distinguished by having muscular, spindle-shaped bodies that taper at both ends, as well as prominent dorsal fins in the center of their bodies.

Great white sharks are frequently depicted in one-dimensional terms as merciless predators who are always looking for food.

The fact is that they each have a unique personality just like us.

They might be outgoing or reserved, some are consistent while others are chaotic and unpredictable.

Sharks are naturally curious and intelligent creatures, and this is especially true when new objects enter their domain.

Sharks are several hundred million years older than dinosaurs and have been proven to be some of the most successful creatures found on our planet.

Their success is a result of their capacity to adapt to environmental factors almost everywhere in the world’s oceans.

Why Great White Sharks Deserve our Protection

According to estimates, humans kill roughly 100 million sharks every year. This amounts to about 200 sharks per minute.

Millions of sharks are killed each year as undesired bycatch in fisheries that are intended to target other species rather than sharks.

Only 5% of the sharks’ bodies are used in the brutal and wasteful practice of shark finning, which alone kills up to 73 million sharks annually.

Sharks have already survived four mass extinction events on our planet that have wiped-out millions of other species! Now, with unsustainable catch rates, humans are pushing shark populations – including great white sharks – to the point of extinction.

Hopefully it is not too late to protect all sharks, including great whites.

If we eliminate sharks from the oceans, we endanger a huge range of marine species and entire ocean ecosystems.

References

International Shark Attack File (2021). The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) is the world’s only scientifically documented, comprehensive database of all known shark attacks. Initiated in 1958, there are now more than 6,800 individual investigations covering the period from the early 1500s to the present.

Martin, R.A., Hammerschlag, N., Collier, R.S., Fallows, C. (2005). Predatory behavior of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) at Seal Island, South Africa. Journal of Marine Biology Ass. U.K, 85: pp. 1121-1135.

Sato, K., Nakamura, M., Tomita, T., Toda, M., Miyamoto, K., & Nozu, R. (2016). How great white sharks nourish their embryos to a large size: evidence of lipid histotrophy in lamnoid shark reproduction. Biology Open, 5(9), 1211–1215. http://doi.org/10.1242/bio.017939

Read More about the Fascinating Great White Shark

Great White: The Majesty of Sharks by Chris Fallows

For most people, sharks and fear go hand in hand. Renowned photographer and conservationist Chris Fallows maintains a more nuanced relationship with the super predator. Fallows’s brilliant photographs present these mighty creatures in a different light. Great White, the first publication to collect Fallows’s work, reveals the sublime beauty of sharks and provides a rare glimpse into the largely unseen world of great whites, hammerheads, and other breeds.

Fallows captures these fearsome creatures both above water, as they intersect with humanity, and below, in their mysterious underwater domain. A one-of-a-kind portrait of the shark and a superlative study of the nature photographer’s art, this book is bound to turn heads and elicit a deep appreciation for the creatures that inhabit our oceans.