Albatrosses are large seabirds with the longest wingspans of any bird in the world, up to 10 or 12 feet. As a biologist, I became intrigued with the flight of the albatross after watching huge Royal Albatrosses soar past us on the Otago Peninsula in New Zealand.

Albatrosses can soar effortlessly for hours at a time without flapping their wings. Using dynamic soaring, albatrosses harness the energy stored in the wind. Young albatrosses can spend the first 6 years of their life at sea, never touching land. They can cover hundreds of miles in one day feeding on fish and squid. Albatross can sleep while flying – but only for seconds at a time.

Albatross flight is an excellent example of how birds can use air currents and thermals to soar long distances without exhausting themselves or expending much energy.

The thing about albatrosses is that they need wind. Albatrosses and wind are inseparable.

Albatross flight is fascinating because it relies on so many different forces: wind shear, gravity, thermals, and drag among others.

Watch my video of a Royal albatross effortlessly soaring past the Waiwhakaheke Seabird Lookout on the Otago Peninsula near Dunedin, New Zealand.

Albatrosses, such as the wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans) routinely fly extremely long distances and cross entire oceans on foraging trips while hardly flapping their wings. They can accomplish these amazing flights primarily by using dynamic soaring, a phenomenon that has intrigued physicists and biologists for well over a century.

Through dynamic soaring, albatrosses take advantage of the consistent ocean winds to provide lift as they weave an S pattern over the wave tops and troughs. It’s an incredible feat of evolutionary engineering! Albatrosses have evolved to become masters the wind and the waves, and by incorporating all the precision turns and headings required for dynamic soaring they are able to fly at almost no cost.

Keep reading to discover how dynamic soaring works! But first, let’s discuss how long albatrosses can stay in the air and how far they can fly.

How Long Can an Albatross Remain at Sea Without Touching Land?

Albatrosses can spend up to six years at sea without touching land.

Albatrosses can live up to 50 or 60, perhaps even 70, years and they spend most of their lives in flight over the open ocean. They only return to land to breed and raise their chicks at nesting sites found mainly on isolated oceanic islands.

There is one spot on the mainland of New Zealand where you can easily get to see nesting pairs and chicks of the Royal albatross – see location and details at the end of this article.

How Far Can an Albatross Fly?

Based on data that scientists have accumulated over the past two decades we’ve learned that albatrosses can travel farther than any other wild creature on the planet. As foraging grounds of all albatross species are pelagic, they need to find productive areas repetitively during the breeding period. Trips of 15,200 km or flights around the world in 46 days have been reported for the wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans).

One Laysan albatross has been tracked for 15,000 miles (over 24,000 km) in one month. Over a lifespan of 50 years, which is the average for most albatrosses, a typical bird can cover more than 3 million miles or nearly 5 million kilometres.

When at sea, most albatrosses frequent the storm zone that girdles the earth in the southern hemisphere. These zones are known by sailors as the famous roaring 40s and the furious 50s because the fierce winds are so consistent.

Not only can an albatross fly far, but it can also fly fast. GPS tracking has revealed that albatrosses are capable of mean ground speeds faster than 80 mph (127 km/h) and can maintain these speeds for more than 8 hours at a time.

How Does Dynamic Soaring Work?

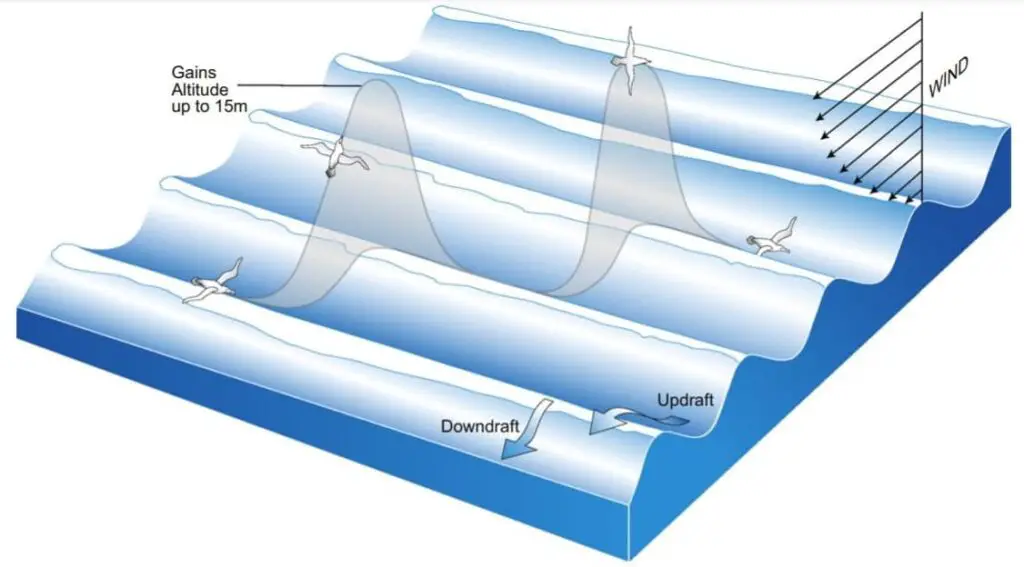

In dynamic soaring, albatrosses take advantage of the changing speeds and directions of the wind relative to the ocean’s surface. Albatrosses are known to use dynamic soaring to fly very long distances without flapping their wings.

According to Woods Hole scientist, Philip Richardson, “dynamic soaring is a technique in which birds exploit the vertical gradient of wind velocity (wind shear) and also temporal variations of wind velocity for sustained energy-neutral soaring.”

The result is that albatrosses fly in a characteristic and distinctive flight pattern consisting of a swooping motion where each swoop ends close to a wave crest. Each swoop begins with a fast flight parallel to and just above the windward side of a wave. This is followed by a turn into the wind and climb of around 30-50 feet (10–15 m), followed by a downwind descent towards another wave and a turn parallel to the wave. The typical time to complete a swoop is around 10 seconds.

The albatross harnesses the energy of the wind by climbing upwards across the wind shear layer by heading into the wind and making a precision turn to descend downwards across the wind shear layer while heading downwind. After this sequence, the albatross turns again to head upwind… and so the soaring continues.

Here is an excellent video from the IEEE showing how dynamic soaring makes flight almost effortless for the albatross.

The close relationship between the swoops and waves suggests that the changes in wind profile relative to the waves is important for sustained soaring by albatrosses. According to some scientists, these dynamics are often overlooked in models of soaring flight.

How Much Energy do Albatrosses Expend While Flying?

Here’s some information that you and your friends might consider truly amazing! I know I do!!

An albatross can do something that no other bird is capable of. It can fly thousands of miles at no mechanical cost. That’s right – albatrosses use less energy flying across oceans than you use to walk around the block. In fact, they might use less energy covering thousands of miles than you use sitting in your lounge chair drinking a beer!

Metabolic studies have shown that an albatross in flight expends hardly any more energy than an albatross sitting on ground doing nothing!

This is the amazing benefit of dynamic soaring. The secret is that they gain more energy from the wind than they expend in flight.

For millions of years albatrosses have been harvesting the wind as they soar vast distances across the oceans!

Using high precision GPS equipment, scientist have been able to track free flying birds to gain a good understanding of the physical mechanisms involved. The research has revealed the amount of energy gain transferred from the wind to the bird.

Studies have shown that the energy gain is achieved by the dynamic flight manoeuvre outlined above, as the bird continually repeats the up-down curve of dynamic soaring while making optimal adjustments to the wind.

Albatrosses demonstrate amazing evolutionary adaptations to living in the extreme environment of the frigid and furious winds of the Southern Ocean storm zones.

What are the Adaptations Necessary for Sustained Soaring?

Albatrosses feature key adaptations necessary to reduce energy expenditures during flight.

The first of these adaptations is anatomical. Albatrosses have an elbow-lock system which keeps their wings open without any muscle activity and, thus, no energy expenditure.

Albatrosses, and many other birds, have a remarkable mechanism that allows coordinated flexion and extension of the elbow and wrist. What makes it particularly remarkable is the way it acts almost automatically and how efficient the action is in terms of energy use. Extension of the wing automatically puts it into flight position with a tendon locking the wing open, while flexion automatically folds it away. These actions position the bones, ligaments, and tendons almost perfectly without much in the way of active muscle contraction.

See an albatross’s elbow-lock system in action.

Check out this video to see how effectively the elbow-lock mechanism works in this dissection of a Laysan albatross (warning – not for the squeamish. The video is slightly gruesome, but instructive. You might also be interested in a dissection video showing how a woodpecker’s tongue can extend several inches by coiling around the head.)

The second adaptation concerns the flight mode of dynamic soaring that we’ve already covered. As we’ve seen dynamic soaring enables albatrosses to gain the energy required for flying from the constant strong winds available on the open ocean.

How Can Albatrosses Sleep While Flying?

Scientists are convinced that it’s very likely that albatrosses sleep on the wing. In a study published in Nature Communications Rattenburge et al. (2016) describe how the frigatebird, another seabird and distant cousin of the albatross, take frequent but very short – seconds-long – naps while flying.

GPS-tracked movements of albatrosses show that they can fly for hours on end, so scientists are confident that they must sleep while in flight.

Interestingly, birds on land can switch from sleeping simultaneously with both hemispheres of the brain OR they can sleep with one hemisphere at a time in response to changing demands for their attention or level of alertness.

Where Can You See Nesting Albatross?

One of the best places in the world to see nesting albatross is on the Otago Peninsula on the South Island of New Zealand. We’ve had the good fortune of visiting this site several times in our world travels and have never been disappointed. The Royal Albatross Centre provides educational materials and, for a fee, the opportunity to view the nesting albatrosses and their chicks. This might be the only place you’ll have a chance to see chicks the size of turkeys!

The nearby Waiwhakaheke Seabird Lookout is free of charge, and you have wonderful opportunities to watch Royal albatrosses soar past on their way to and from the nesting site. This is where I managed to capture my slow motion video of an adult albatross soaring past. Here’s a 360 view of the lookout.

Located on the windswept end of the Otago Peninsula, Taiaroa Head (called Pukekura by the Maori) is world renowned as the only mainland colony of albatross in the Southern Hemisphere.

At Taiaroa Head, Royal Albatross return to land to breed and raise their young – one chick every two years. Royal albatross usually mate for life and meet at the same nesting area each time.

Albatrosses have one of the longest incubation periods of any bird and parents share incubation duty in shifts of eight days on average over a period of about 11 weeks. Afterwards chicks are left unguarded, except for feeding visits, until they fledge at about eight months.

Watch this young Royal albatross testing her wings in the gusting winds of Taiaroa Head.

This helps the nestling build her flight muscles for the day when she leaves the nest in September, heading off on her own to feed over great stretches of the Pacific Ocean and not touching land for several years.

After successfully raising a chick, the parents leave the colony to spend a year on their own feeding at sea. After a year off they will return to breed again, completing a two-year cycle.

Adolescents return to look for a mate after 3 to 8 years on their own. Once back at the same breeding grounds they left years earlier, the male birds make a display of stretching their wings, lifting their heads, and screaming raucously. All in an effort to catch the eye of an admiring female, to be followed by elaborate courtship rituals.

Male birds all over the world (and males in general!) must work hard to impress females and gain the opportunity to mate! Learn more about some of the tricky dances and demanding songs in my article on sexual selection: Why Are Male Animals More Beautiful and Colorful? Sexual Selection! With Photos.

Here’s an entertaining video showing the complex courtship dance of the Laysan albatross.

Where Can You See an Albatross Up Close?

If you are ever near Dunedin, NZ, and the Otago Peninsula, you would have great opportunities to see albatross up close – on dry land and out on the water.

For a wonderful wildlife viewing experience, we can highly recommend the friendly and informative Monarch wildlife cruise.

We slowly drifted alongside albatross feeding on the ocean surface without bothering them and had lots of excellent photo opportunities.

The captain took the boat in close for a great view of NZ fur seals on the rocks and in the water around their breeding rookeries. When the weather was cool and unsettled on our trip, they provided us with cozy waterproof jackets.

In Summary, Some Cool Facts About the Albatross

- can spend 6 years or more at sea without touching land

- only birds capable of flying thousands of miles without expending energy

- parents can fly more than 10,000 miles to deliver one meal to the chick

- travel farther than any other wild creature on the planet

- soar for several hours without flapping their wings

- capable of flying faster than 80 mph (127 km/h) for more than 8 hours

- able to fly while half-asleep

- have special salt-excreting glands that allow them to drink saltwater and a highly-developed sense of smell for tracking down prey

- they cannot dive deep or swim underwater like penguins and some other sea birds. They pluck fish and squid that swim near the surface of the water.

Sobering Facts About Albatrosses

- Of the 21 albatross species, 19 are threatened or endangered

- The Chatham albatross is critically endangered, with only about 11,000 birds remaining

- In some places the number of albatrosses has declined by half in the past 20 years

- Biologists regard them as the world’s most threatened family of birds

References

Richardson, P. L., 2011: How do albatrosses fly around the world without flapping their wings? Progress in Oceanography 88, 46-58.

Richardson, P.L., Wakefield, E.D. & Phillips, R.A. Flight speed and performance of the wandering albatross with respect to wind. Mov Ecol 6, 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-018-0121-9

Rattenborg, N., Voirin, B., Cruz, S. et al. Evidence that birds sleep in mid-flight. Nat Commun 7, 12468 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12468

Sachs G, Traugott J, Nesterova AP, Dell’Omo G, Kümmeth F, Heidrich W, et al. (2012) Flying at No Mechanical Energy Cost: Disclosing the Secret of Wandering Albatrosses. PLoS ONE 7(9): e41449. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041449

Header photo of albatrosses riding gale-force winds on the open ocean by Fer Nando on Unsplash, with thanks.

See Our TOP Articles for More Fascinating Creatures

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex, Detachable Penis)

- How Smart are Octopuses? Are Octopuses As Intelligent as Dogs?

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How Can they Hunt without Brains?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on One?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos so Aggressive? Why do they Kill People?)