We’ve had the good fortune of sitting quietly and watching wild platypuses swimming and feeding in their native habitat in Eungella National Park, Australia. The duck-billed platypus is often considered the most unique and bizarre mammal on the planet with some of the most unusual adaptations you will find anywhere. Let’s dive into some of the mysteries surrounding this small, venomous, egg-laying mammal!

Platypus males have venomous spurs on their hind feet with enough venom to kill small animals and cause excruciating pain in humans. Females don’t have venom or spurs. Platypuses are mammals, although they lay eggs instead of bearing young live and produce milk without having nipples. These weird mammals also have electrical receptors for finding prey, hard plates instead of teeth, and duck-like bills.

Platypuses are perfectly adapted to life in rivers and streams with their webbed feet, flat tails, and water-repellant fur. You might be fortunate to see a platypus in the wild if you spend enough time in its native habitat along the rivers of eastern Australia, including Tasmania.

Platypus Males Have Venom, but Can They Kill You?

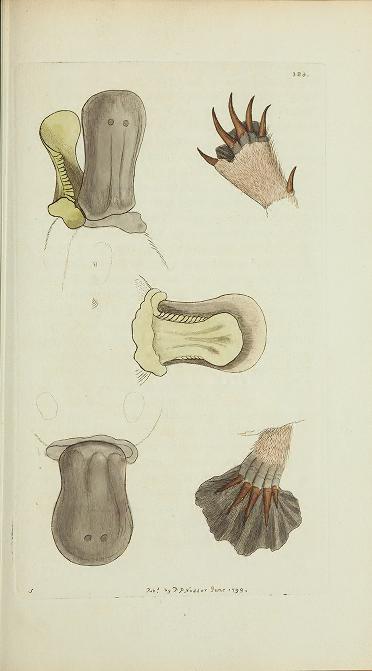

Male platypuses have venomous spurs — a secret weapon that must have made a painful impression on the first Westerners who tried to handle one. Truly a nasty surprise!

The male platypus is one of the few venomous mammals alive today, with a spur on each hind foot connected to a gland that produces toxic venom.

There’s enough venom in a platypus spur to kill small animals, perhaps even dogs although this has not been well-documented.

The venom causes excruciating local pain in humans, although there’s no record of a human dying from a platypus sting.

There is a medical report (Fenner et al. 1992) of a 57-year-old man who was stung on the right hand by both spurs of a male platypus. The pain was so intense that first aid could not help. Even narcotics administered intravenously at the hospital proved inadequate.

The only thing that stopped the pain was a nerve blocker. Afterwards, narcotics were required for several days. The patient spent six days in hospital, and his hand remained painful and swollen, with little mobility, for three weeks. He couldn’t use his hand properly for three months.

There’s no antivenin available for platypus stings, so it wouldn’t be a good idea to try to handle a live male platypus!

Males can use their venomous spurs as a defense against predators, but the primary purpose is for fighting other males during mating season. Venom production increases during the mating season when males fight each other over access to breeding females. The venom has a chemically complex composition that can temporarily render envenomated males partially paralyzed during the breeding season. Males have killed one another with multiple spurring but, as far as I can discern, this has only been recorded for males in captivity.

Females do not have spurs, although juvenile females show signs of vestigial spur sheaths that disappear within the first year.

Unsheathing your spur to strike another male must be the platypus way of getting your rival to crawl into a corner while you get to hang out with the females!

Here’s a video showing the male’s venomous spur by the Natural History Museum:

Fascinating Adaptations of the Platypus:

- leathery bill that might look duck-like, but really a sense organ with thousands of receptors for taste, touch, and electroreception

- venomous spurs and enough venom to kill small animals

- hard plates instead of teeth

- lay eggs instead of giving live birth, even though they are mammals

- feed their young milk without having nipples

- webbed feet

- a flat tail

- water-repellant fur

Platypuses have some of the most unique adaptations of any animal on the planet.

The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is a monotreme and, even though it is a mammal, it still lays eggs. Every other mammal, except for the echidna, has evolved to give live birth. Egg-laying must work well for the platypus, since they’ve been successful for many millions of years!

How can a Mammal Lay Eggs?

Most mammals do not lay eggs, but the earliest mammals did, and monotremes – the platypus and echidna – still do.

Monotremes are the only mammals that lay eggs, but they also feed their young milk. The word ‘monotreme’ refers to the fact that they have only one body opening for both waste and eggs to pass through, the cloaca. Take my word for it, you don’t want to check this out for yourself!

There aren’t many mammals that begin life by breaking out of an egg! In fact, there are only two – the duck-billed platypus and the spiny echidna. These unique mammals lay small, spherical eggs with one youngster inside each. Guess what the young platypus inside an egg is called? A puggle. I didn’t make that up… it’s the real word for a baby platypus or echidna.

Platypuses don’t have pouches, and the mother curls her body and tail around the eggs for 10-12 days to keep them warm. Once the puggle is fully formed, it will push its way out of the egg. Is it still called hatching if it’s a mammal emerging from the egg, rather than a bird? Yes, sounds strange, but it’s true.

How can the platypus mother feed its young without breasts or teats? They produce milk in their mammary glands, but instead of suckling the young, the mother oozes milk into grooves in the abdominal skin, and the babies lap it up instead of latching onto a teat. Young are nursed like this for about five months.

The following video offers a rare look into a platypus nest with two youngsters!

Why do Platypuses have Duck-like Bills?

The bill might look duck-like, but it is really a sense organ featuring thousands of highly refined receptors for taste, touch, and electroreception.

Platypus feed primarily on aquatic crustaceans and insect larvae and their bills are adapted for sensing food in the murky water and for probing into the soft mud and sediment between rocks and vegetation. Even though the platypus’ bill looks duck-like, it is rubbery, soft, and flexible, not at all like a bird’s beak. The platypus has nostrils at the tip of its bill, but it doesn’t have a great sense of smell.

Platypuses spend much of their time swimming close to the bottom sweeping their bills back and forth ‘looking’ for food… except they keep their eyes closed! In fact, platypuses close their nasal cavity and their eyes when swimming, relying on other senses to detect prey — especially their electric receptors.

In another interesting twist, young platypuses have molars, but the adults are toothless. Adults lose their teeth and instead have hard, keratinous plates on each jaw to masticate their food. The front part of each plate is used to chop food; while the back part is flat and used for crushing.

Having hard plates in each jaw must be a useful adaptation for catching and eating their prey. Platypus diets are often dominated by relatively large aquatic invertebrates such as the larvae of caddisflies, mayflies, dragonflies, and damselflies.

They can also eat crusty crustaceans with crunchy carapaces! In Australia, there are many species of freshwater crayfish commonly known as yabbies. The most common and widely distributed species is the common yabby with the impressive Latin name of Cherax destructor. The destructor might sound tough, but its no match for a hungry platypus!

How do Platypus Use Electroreceptors?

The leathery bill of the platypus has a complex system of sensors, including electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors, providing electric and tactile senses. The electroreception sense is unique to platypus among all the mammals.

The specialized electroreceptors are housed in pores on the skin of the platypus’s bill and frontal shield and are connected to the trigeminal nerve. Using these receptors, the platypus can sense the weak electric fields produced by the muscles of underwater organisms such as larvae, worms, crustaceans, and other prey species.

Since many of these animals are hiding under the mud and rocks, we can see that being able to detect minute electric fields would provide the platypus with a huge advantage in finding its prey.

Electroreception appears to be the platypus’ primary sense for finding their prey, given that they hunt with their eyes and ears closed!

How do Platypus Feed?

Platypuses spend mornings and evenings actively hunting for food and spend the warm part of the day in their burrows.

They are skillful swimmers perfectly adapted to their aquatic lifestyle, paddling with their webbed front paws while maneuvering with their back paws and flat beaver-like tail. As they swim near the river bottom, they sweep their sensitive bills from side to side searching for electrical impulses from their prey hidden beneath the mud and rocks.

Platypuses can stay underwater for several minutes, storing bits of prey in their cheek pouches before coming to the surface to grind and swallow the food. When we were watching platypuses in the wild, the best way to spot them was to watch for the ripples created as they masticated their food at the surface.

These animals eat a lot of food, around one-fifth of their body mass each day. Females bearing young eat even more. They often hunt for 10 to 12 hours or more per day to find enough aquatic invertebrates to meet their needs.

Here’s a great overview of the platypus from the San Diego Zoo:

The Gear We Love to Travel With

We love to travel in search of exceptional wildlife viewing opportunities and for life-enhancing cultural experiences.

Here is the gear we love to travel with for recording our adventures in safety and comfort:

- Action Camera: GoPro Hero10 Black – we find these waterproof cameras are invaluable for capturing the essence of our adventures in video format. Still photos are great, but video sequences with all the sights and sounds add an extra dimension. I use short video clips to spice up many of my audiovisual presentations.

- Long Zoom Camera: Panasonic LUMIX FZ300 Long Zoom Digital Camera – I love this camera for its versatility. It goes from wide angle to 28X optical in a relatively compact design. On safari in Africa I’ve managed to get good shots of lions that the folks with long lenses kept missing – because the lions were too close! I also like the 120 fps slow-motion for action shots of birds flying and animals on the move. I call this my “bird camera.”

- 360 Camera: Insta360 ONE R 360 – 5.7K 360 Degree Camera, Stabilization, Waterproof – see my article How to Take Impossible Shots with Your 360 Camera. This camera is literally like taking your own camera crew with you when you travel! Read my article and you’ll see why.

- Backpack camera mount: Peak Design Capture Clip

- Drone: DJI Mini 2 (Fly More Combo) – this mini drone is made for travel!

- Water Filtration: LifeStraw Go Water Filter Bottle

- Binoculars: Vortex Binoculars or Vortex Optics Diamondback HD Binoculars (good price)

Are Platypus Related to Birds or Reptiles?

The platypus is classified as a mammal because it has fur and feeds its young milk, but it also has bird and reptile features.

There are more similarities between platypus and birds than there are between platypus and humans. Their body temperature is lower than most mammals, a feature that has more in common with reptiles.

Scientists believe all mammals evolved from reptiles, and the animals that became platypuses and those that became humans shared an evolutionary path until about 100 million years ago when the platypus branched off. Unlike other mammals, the platypus retains some of the characteristics of snakes and lizards, most notably the painful venom that males produce.

When the platypus genome was first analyzed and published in 2008, researchers were surprised to find that the genes which determine sex in a platypus are more like those of a bird than those of a mammal.

The platypus has 10 sex chromosomes while humans have two sex chromosomes. In case you feel shortchanged, you can be thankful that you’re not a bird – or a platypus, I guess!

Are Platypuses Primitive Mammals?

Let’s consider the evolution of mammals. Mammals split away from reptiles approximately 165 million years ago. Then, over 120 million years ago, early ancestors of the monotremes split away from the other early mammals, resulting in two lineages. One lineage led to the monotremes – the platypus and echidna of today; and the other lineage later split again, giving rise to placental mammals like us as well as the marsupials like the kangaroo.

Since that time, all three lineages have had an equal number of years to evolve – over 100 million years in fact. Based on a platypus fossil from southeastern Australia we know that platypuses roamed the planet as far back as 122 million-years ago – during the middle of the dinosaur era.

Although platypuses branched off early on the mammalian tree of life and share some features with reptiles and birds, they are perfectly adapted to their environment in the rivers of eastern Australia. Rather than being primitive, platypuses are highly specialized and successful within their ecological and reproductive niches.

That’s how natural selection works. Individuals that are best suited to their environment get to pass on their genes, which is what the platypus has been doing very successfully over many millions of years since they swam with the dinosaurs!

Watch this short 2 min video to learn more about the monotremes of Australia:

First Platypus Specimen Was Considered a Hoax

Imagine people’s surprise when the first specimens of platypus sent from Australia arrived in England in the late 18th century. British scientists looked at this strange creature with its duck bill, flat tail and beaver-like pelt and immediately thought it was a hoax. In 1799, the English zoologist George Shaw wrote “It naturally excites the idea of some deceptive preparation by artificial means.”

Shaw continued, “Of all the Mammalia yet known it seems the most extraordinary in its conformation; exhibiting the perfect resemblance of the beak of a Duck engrafted on the head of a quadruped.”

It was only with “the most minute and rigid examination,” Shaw wrote, that “we can persuade ourselves of it being the real beak and snout of a quadruped.”

Shaw also released the first published illustration of the platypus, based on a sketch from John Hunter. the governor of New South Wales.

Watch this National Geographic video for more fascinating facts about the platypus.

References

Bino, G., Kingsford, R.T., Archer, M., Connolly, J.H., Day, J., Dias, K., Goldney, D., Gongora, J., Grant, T., Griffiths, J. and Hawke, T., 2019. The platypus: evolutionary history, biology, and an uncertain future. Journal of mammalogy, 100(2), pp.308-327.

Fenner PJ, Williamson JA, Myers D. Platypus envenomation–a painful learning experience. Med J Aust. 1992 Dec 7-21;157(11-12):829-32. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb141302.x. PMID: 1454022.

You might be interested in reading my article about the koala — probably the dumbest mammal on the planet with a strangely shrunken brain!

Check out Our Top Articles for even more Fascinating Creatures

- How Do Wolves Communicate? (Why Do Wolves Howl?)

- What do Red Pandas Eat? Is the False Thumb Used for Feeding?

- Can Octopus Arms Grow Back? Are Regenerated Limbs Just as Good?

- How Many Senses Do Sharks Possess? Electroreception Made Easy!

- How to Keep Bird Feeders Clean (Top Tips for Avoiding Salmonella)

- Are Wolf Dogs Safe or Dangerous? Do Wolves or Wolf Dogs Make Good Pets?

- Koala Brains – Why Being Dumb Can Be Smart (Smooth Lessons from Natural Selection)

- Why do Lions Have Manes? (Do Dark Manes Mean More Sex?)

- How Do Lions Communicate? (Why Do Lions Roar?)

- How Dangerous are Stonefish? Can You Die if You Step on a Stonefish?

- What Do Animals Do When They Hibernate? How do they Survive?

- Why are Deep Sea Fish So Weird and Ugly? Warning: Scary Pictures!

- How do Octopus Reproduce? (Cannibalistic Sex and a Detachable Penis)

- Do Jellyfish have Brains? How can Jellies Hunt and Swim without Brains?

- Leaf Cutter Ants – Surprising Facts and Adaptations; with Pictures and Videos

- Irukandji Jellyfish Facts and Adaptations; Can They Kill You? Are they spreading?

- How to See MORE Wildlife in the Amazon: 10 Practical Tips

- Is it Safe to go on Safari with Africa’s Top Predators and Most Dangerous Animals?

- What to Do if You Encounter a Bullet Ant? World’s Most Painful Stinging Insect!

- Why do Octopus have 3 Hearts, 9 Brains, and Blue Blood? Smart Suckers!

- How Do Anglerfish Mate? Endless Sex or Die Trying!

- How Smart are Crocodiles? Can They Cooperate, Communicate…Use Tools?

- How Can We Save Our Oceans? With Marine Sanctuaries!

- Why Are Male Birds More Colorful? Ins and Outs of Sexual Selection Made Easy!

- Why is the Cassowary the Most Dangerous Bird in the World? 10 Facts

- How Do African Elephants Create Their Own Habitat?

- What is Killing Our Resident Orcas? Endangered Killer Whales

- Why are Animals of the Galapagos Islands Unique?

- Where Can You See Wild Lemurs in Madagascar? One of the Best Places

- Where Can You see Lyrebirds in the Wild? the Blue Mountains, Australia

- Keeping Mason Bees as Pets

- Why do Flamingos have Bent Beaks and Feed Upside Down?

- Why are Hippos Dangerous? Why Do They Kill People?

- Are Komodo Dragons Dangerous? Where Can you See Them?